Greece: Trapped in island camps

"Speaking figuratively, I see migration as a huge tree. The tree’s roots symbolise common or shared reasons and motivations…. People leave to go to other countries, dreaming of a better future for their children, fleeing war, oppression, and violence, hoping to live beyond the reach of misery and conflicts—all while carrying their tragedies and their fears, their trauma and their hopes."

Moria camp in Lesbos, designed to hold 2,757 people, housed approximately 15,000 women, men, and children until it was destroyed by fire in September 2020. The camp had become a place of violence, deprivation, suffering, and despair.

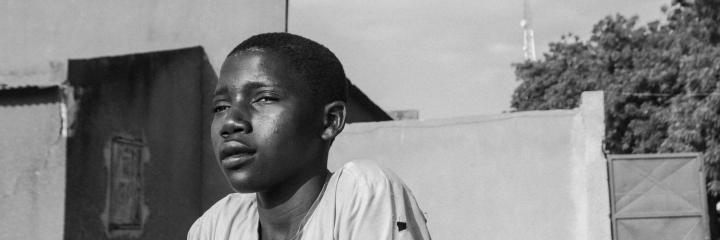

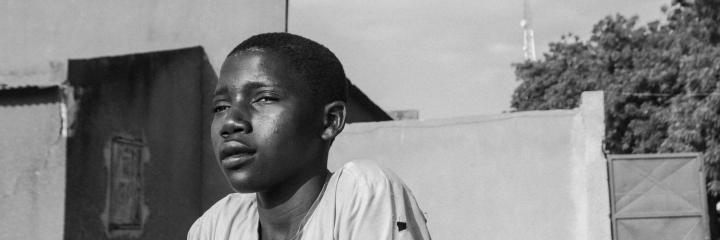

© Enri Canaj/Magnum PhotosTens of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers are held in camps on the Greek islands, crammed together in extremely precarious and appalling conditions. The situation has gotten even worse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The camps’ unhealthy living conditions and overcrowding are conducive to the spread of COVID-19. Given the lack of appropriate health services and very limited medical care, the risk that the virus could spread among camp inhabitants has been and remains a cause for concern. How can people comply with preventive measures such as social distancing and handwashing under such conditions? Families of five or six must sleep in spaces smaller than three square metres [32 square feet]. Since March 2020, pandemic-related curfews and restrictions on asylum seekers’ movements in Moria have been extended seven times for a total of more than 150 days.

Canaj was there on 9 September 2020, when several fires broke out in Moria refugee camp on Lesbos, destroying its infrastructure and forcing 12,000 people to flee yet again.

Several fires broke out in quick succession on 9 September, destroying the entire camp and forcing refugees to flee once more.

© Enri Canaj/Magnum Photos

"Our teams saw the fire spread through the camp throughout the night, said Marco Sandrone, MSF project coordinator on Lesbos. Everything was burning. We saw huge numbers of people fleeing the flames, but they had no idea where to go. The children were terrified, and the parents were in shock."

A woman expresses the pain caused by burns on her skin from tear gas that was fired by police during clashes near the town of Mytilene on 12 September.

© Enri Canaj/ Magnum Photos“It’s shameful what people face on the island every day,” Canaj said. “These fires are only the tip of the iceberg.” In Greece, tens of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers are living in camps after agreements between the European Union and Turkey took effect in March 2016. The accords, which MSF and multiple organisations have criticized, have trapped thousands of men, women and children in unhealthy, degrading, and dangerous conditions.

The overcrowded camps, with their harmful conditions, create tensions among the residents. In 2019, Vasilis Stravaridis, general director of MSF Greece, said: “In Vathy, on Samos, more than half of the people living in the camp sleep in tents or under plastic tarps, surrounded by garbage and human faeces.”

Magulah and her husband, Mohammad, had been in Moria camp since July 2019. Originally from Afghanistan, they have six children, but not all of them arrived together. “During a failed attempt to reach Greece from Turkey in 2018, we were separated from our children,” said Magulah. “One is now in a refugee camp in Germany. We also have a 14-year-old son who is in a hospital in France. We were able to regain contact with him two days ago for the first time in two years. He has panic attacks and mental health problems.”

Before Moria camp was destroyed, she described life there: “Everyone is suffering. The days pass, empty. All we do is wait in line. There are lines for food and for water, and we have to wait for more than an hour to use the toilet. We can’t stay here any longer.”

© Enri Canaj/ Magnum PhotosToll on mental health

“Now, with the quarantine, it feels like we’re in prison,” said Said Abbasi, a refugee on Lesbos who was living in Moria camp before the fires. “I have to ask permission from the camp to get medicine for my baby, but they won’t let me leave. I just want to cry and scream, I have so much pain in my soul. But I don’t have a safe place to do it.”

© Enri Canaj/ Magnum PhotosEveryone here faces obstacles to obtaining medical care. MSF’s teams of psychologists work to provide mental health support, particularly for people suffering from depression, anxiety or psychosis, and to assist victims of torture. Between 2019 and 2020, the mental health clinics on the islands of Chios, Lesbos, and Samos treated 1,369 patients, including many people who were experiencing severe mental illness, particularly post-traumatic stress and depression. More than 180 of the people treated by MSF had suffered injuries due to self-harm or attempted suicide. Two-thirds were children; the youngest was only six years old.

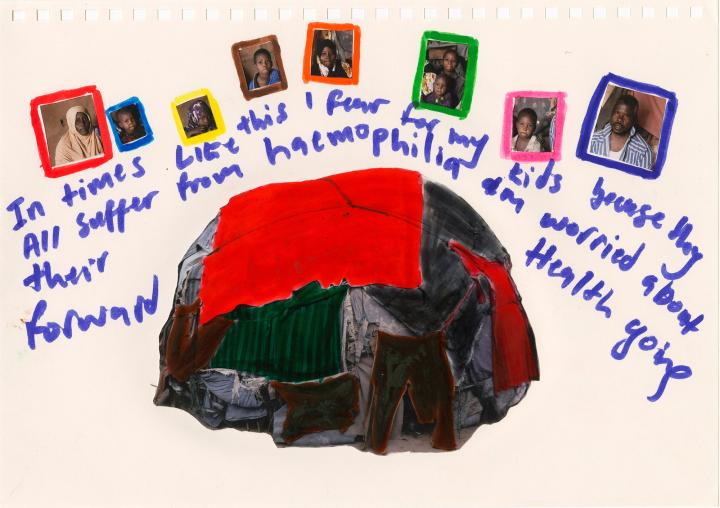

Nine-year-old Yasin drew a picture of people fighting in the camp where he lived on Lesbos. Greece 2020

© Enri Canaj/Magnum Photos

“I have a problem with my kidney,” Golnegar said. “I’m suffering. I have headaches every day, but although I’ve tried to see a doctor in the camp or at the local hospital, I haven’t been able to. All my children have insect bites on their bodies and they often complain that they feel sick, but I can’t do anything for them.”

Her husband adds, “We just want a safe place for our children. We came here to save them from the war and send them to school, but instead we ended up in this camp, waiting in limbo for almost a year.”

"We just want to start a peaceful life and send our children to school. That’s only possible on the Greek mainland or in other European countries. How long will we have to stay in this makeshift camp?"

MSF’s health promotion team handles an essential part of the organization’s work at the Vathy reception centre on Samos. It involves providing preventive health education and ensuring that the people living in the camp can obtain care from MSF’s projects.

© Enri Canaj/Magnum PhotosBreaking free from a feeling of imprisonment

“People confront their difficulties, which shows me just how strong and extraordinary we are as human beings,” said Canaj. “The communities come together and help each other. These actions demonstrate that despite dehumanizing conditions, the care that people show to each other within the migrant communities is very present and alive. I strongly believe that that’s what nourishes the soul of those who survive on the island every day.”

Khalil al Khalil is 67. He is originally from Syria and suffers from chronic pneumonia and high cholesterol. He lives in Vathy camp on Samos in a makeshift shelter with his young son and eight-month-old daughter. “There are no doctors and no medicine in Vathy camp,” he says. “I’m afraid of COVID-19 and I try to isolate myself in my tent. If it reaches the camp, only God will be able to save us.

© Enri Canaj/ Magnum Photos"When we were in Syria, we imagined that we would be treated with respect and dignity in Europe. We thought it would be safe. My only wish is to live a peaceful life with my children, but to do that, we need Europe’s help."

Canaj himself was forced to leave Albania at the age of 11. He feels a deep empathy for the people he photographs. “I know what it means to be trapped, to be undocumented for years, to live in danger,” he said. “All those feelings came back when I was photographing these people and their journeys and stories. Photography helped to ease the feelings I have from all those experiences. I am no longer a passive spectator of reality. And thanks to that, I have found an opportunity to express myself.”

In spite of everything, many refugees have organized to create a semblance of normal life.

“I think the sea represents that bittersweet mix I’ve already talked about,” said Canaj. “Thousands of people have reached Europe by the sea. Many did not succeed. Some bodies have been recovered, but others remain in the waters’ depths. It’s also now where children play in the afternoon. Because these people lack the most basic facilities, the sea is where they bathe, wash their clothes… It even provides them with food.”

Symbol of the European Union’s failed migration policies

Today more than ever, Moria and all of the camps symbolise the failure of the EU’s migration policies. Thousands of vulnerable people have inadvertently become protagonists in a true Greek tragedy.

“When someone arrives from a country torn apart by war, you can’t just slam the door in their face and say, ‘Enough—that’s enough!’” says Canaj. “The communities come together and help each other, despite the dehumanizing living conditions. Good will and the care shown to others within the migrant communities are very present and alive. We can all learn not just from our own experiences, but also from our new neighbours, who have brought their own cultures, traditions, and colours, as well as their pain and their strength… There is so much to learn from other people. I strongly believe that that’s what nourishes the soul of those who survive on the island every day.”

Women line up to get water days after the fires destroyed Moria camp and left them homeless on the island of Lesbos. Greece 2020.

© Enri Canaj/Magnum PhotosLatest photo-reportages

Sudan: Refugees at the border by Thomas Dworzak, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack by Newsha Tavakolian, 2021

Mossoul, When The Birds Will Fly Again by Nanna Heitmann, 2021