Niger, children of the rain

Magaria, Niger. 31 July 2021

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosPhotos: Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum Photos

Text: Ahmad Samro, MSF Programme Manager, who is originally from a village in Zinder

In Magaria in South Niger, many people still live off agriculture in the villages where they were born. Every year, when the rainy season and the lean season begin, malaria and malnutrition rise steeply. These seasonal peaks hit children under five and their families particularly hard. Since 2005, MSF has been working directly with communities and the authorities to increase the collective effort to respond to the surging needs. Limiting the mortality rate among young children is a shared challenge in a place where many are struggling to survive. This is an ongoing battle for the MSF teams on the ground, added to the other difficulties faced by the country, one of which is the severe climate change in Africa’s Sahel. In the region of Zinder, Zied Ben Romdhane spent ten days capturing the lives, culture and habits of the people here as they grapple with climate change, malnutrition, malaria and socio-economic challenges.

Zinder, Niger. Belbeja 24 July 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosEncountering difference

“I was very young when I realised that there were other values and other cultures that, rather than weakening us, teach us to discover difference and to nourish ourselves from it. And a large cultural gap between two people sometimes seems non-existent. That’s a thought that came to me as I recall those days with Zied, the Tunisian photographer who came to see and understand my country.

I was always going back and forth between my home region and the rest of the country for my studies and other jobs I did. Then, when I joined MSF’s international teams, I started commuting between Zinder and the rest of the world. But I always came back. Going away is heartbreaking, but coming back is also painful. We witness suffering and human tragedy and, unconsciously, pass it on to our loved ones. Yet, wherever I’ve been, I’ve always tried not to subscribe to one fixed school of thought, not to reject cultures, and I’ve always seen richness in difference.

Zinder, Niger. 24 July 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosI’m from the Tuareg culture, which predominates in the Zinder region. But our land is actually a multicultural mix of Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri… This ethnolinguistic mixing has given birth to a new culture suffused with the pride that characterises us. It’s worth mentioning that Zinder was the country’s first capital, but due to the lack of water the authorities relocated. This shows how sometimes the fate of a territory can be rather fortuitous...

A land of mixing, under the photographer’s gaze

I’ve always been attached to my Tuareg culture, in which poetry, storytelling and oral culture hold essential places. But today, those stories convey the idea that time has stood still in its ancestral traditions, and we are nostalgic for them. The truth is, the past is over and we must accept that.

Zinder, Niger. 5 August 2021

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum Photos

Zinder, Niger. 24 July 2021

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum Photos

Zinder, Niger. 30 July 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum Photos

Zinder, Niger. Belbeja 24 July 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosI’ve seen this region change. From a demographic point of view, the pressure on the land is huge. With land being passed on through inheritance, the fields are becoming increasingly fragmented, making it necessary to change the type of crops grown. Moreover, land that used to be occupied by livestock is now given over to agricultural crops, which is upsetting the economic balance. There are repeated food and nutrition crises that impact the population to varying degrees. The 2005 crisis, which prompted me to join MSF, gained a lot of attention, but these problems are ongoing here. Traders offer credit, but the price fluctuations mean that families can end up paying up to four times the amount they borrowed. The Zinder region borders the regions of Maradi and Agadez, where there are heightened security tensions, which also puts pressure on Zinder. Finally, climate change is having a real impact here; the rainy seasons have been disrupted and farmers no longer know when to sow their crops. The floods of recent years and soil depletion are destroying the fragile balance of this region. So when it was proposed to bring a photographer to capture Niger in 2021, particularly my region, I offered to accompany him.

Zinder, Niger. 25 July 2021. The start of the rainy season, which brings a rise in cases of malaria.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum Photos

Magaria, Niger. 3 August 2021. A baby receives a treatment in MSF’s paediatric unit in Magaria.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosWe’ve been doing the same thing for years; I thought maybe it was time to get an outsider’s view, a professional eye, to approach malnutrition from a different angle. Malnutrition and malaria are wreaking havoc on families, and medical care is difficult to access due to distance and cost. MSF has been present throughout the region for years and progress has been made thanks to the collective commitment of caregivers, communities and the authorities. But this chronic crisis still takes many lives. With the photographer’s help, I thought we might be able to shed light on a deeper aspect of this situation. Above all, I wanted us to capture the causes and not only the visible consequences in everyday life and the wide open spaces. I’ve always loved wide open spaces...

Magaria. 31 July 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum Photos

Magaria. 4 August 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosThe intensity of life in the photographic moment

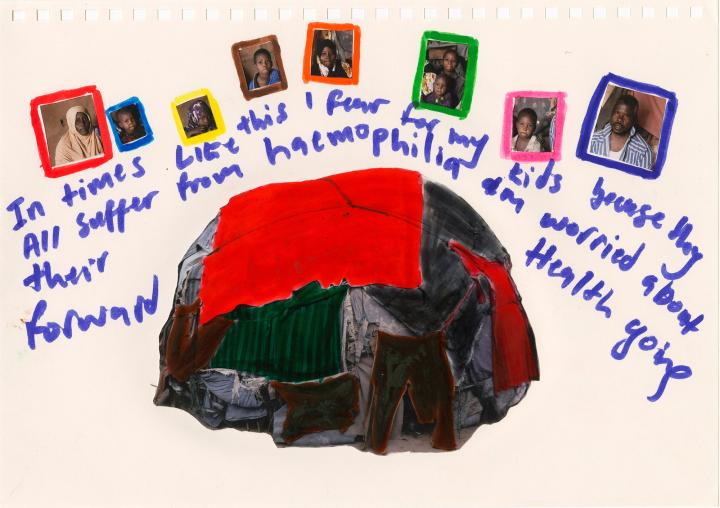

When Zied arrived, I gave him a basic briefing so that he understood where he was, trying not to colour his vision or influence his perception. Then he was free most of the time. He’s quite autonomous and adaptable, and knows how to get people to accept him. But I didn’t leave him complete freedom either. I think we found a middle ground together. Zied accompanied me in my day-to-day life and captured whatever he wanted. He is insatiable, but in a positive sense! People enjoyed watching Zied take his photos and now, when I bump into them, they talk about that moment. They also saw in him, as a photographer, a way to be heard, or at least to convey a few messages.

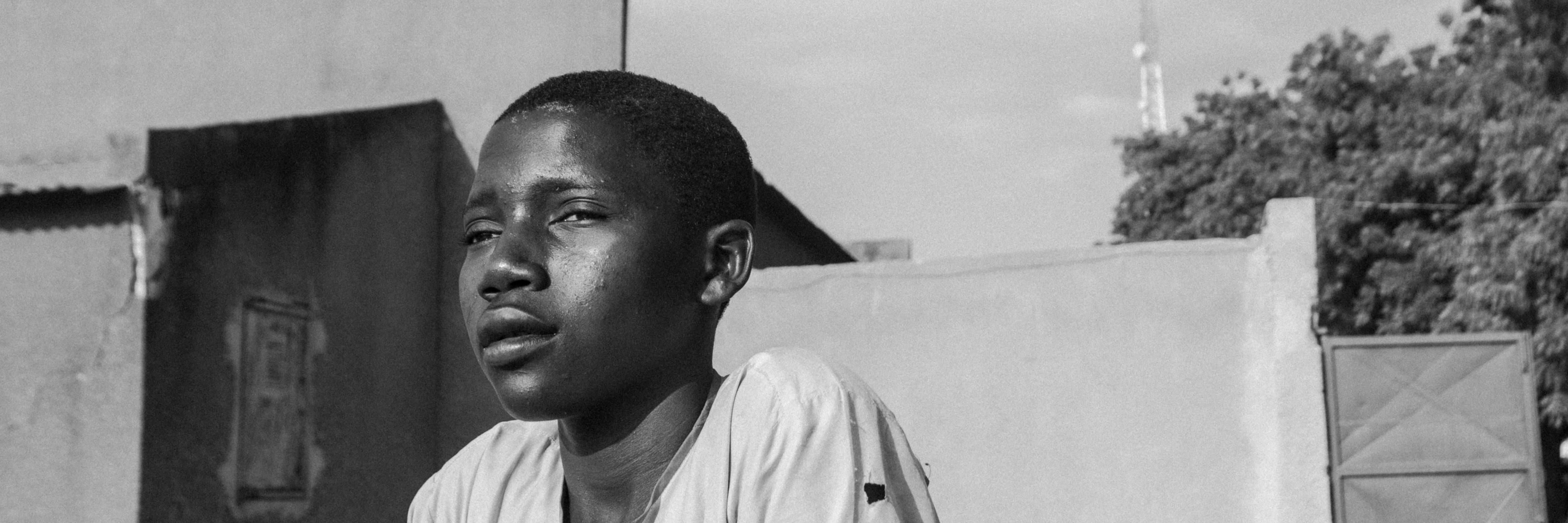

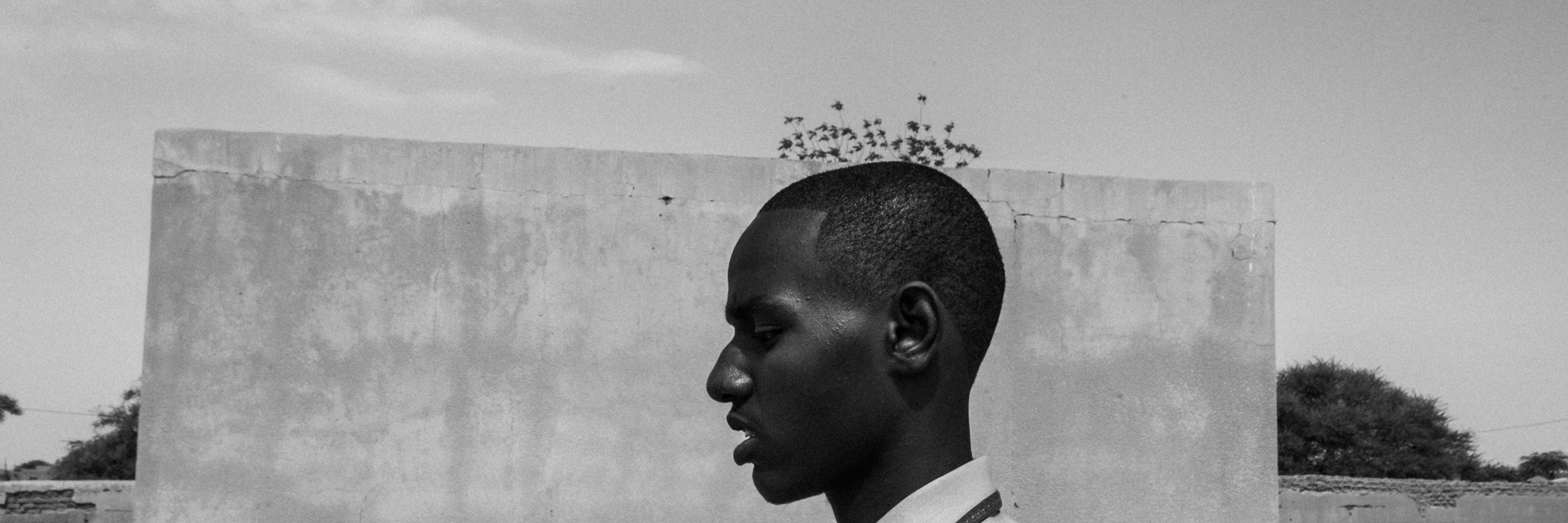

I thought it was important that we see women’s daily lives because the rest of the country has changed and only rural women have remained excluded from those changes. The workload on women and children’s shoulders remains huge and I’m aware of its consequences on their health. We visited more than ten villages in the agricultural area, the pastoral area and the buffer zone between the two. The chance encounters we had determined which families were photographed. Zied is a neutral professional who takes pictures according to what he feels. The result is a jumble of everyday life captured in the moment. And in that frozen moment, we see the intensity of life. When I was little, my father had anthropologist friends who took pictures. The prints would reach us months and months after their visit. I remember that looking back at those moments, recorded on paper, always gave me a peculiar feeling. I was soothed by the images that were both memories of the past and a present moment shared by those of us leafing through the album. Unlike video, a photo is a freeze-frame. It speaks to us silently, makes us think. At first glance, every shot taken by Zied takes me back to my environment, to what I know. But if I pay close attention, I see something more artistic. We become objects or subjects, and the faces in the foreground of the photo seem bigger than in reality. The beauty of that instant shows itself.

I don’t want to send a particular message to the people who see Zied’s pictures. The only thing I would ask of them is that they look with intensity; I would like them to see my daily life, my riches, my smiles, my environment. Perhaps they will see my pain. Maybe they will tell me something or share something with me, prompted by what they have seen of me in those moments. It’s what they say to me that matters. I want to give them the freedom to see the difference in me through their own lens, and for that difference to be viewed as an asset.”

Zinder, Niger. 30 July 2021.

© Zied Ben Romdhane/Magnum PhotosLatest photo-reportages

Sudan: Refugees at the border by Thomas Dworzak, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack by Newsha Tavakolian, 2021

Mossoul, When The Birds Will Fly Again by Nanna Heitmann, 2021