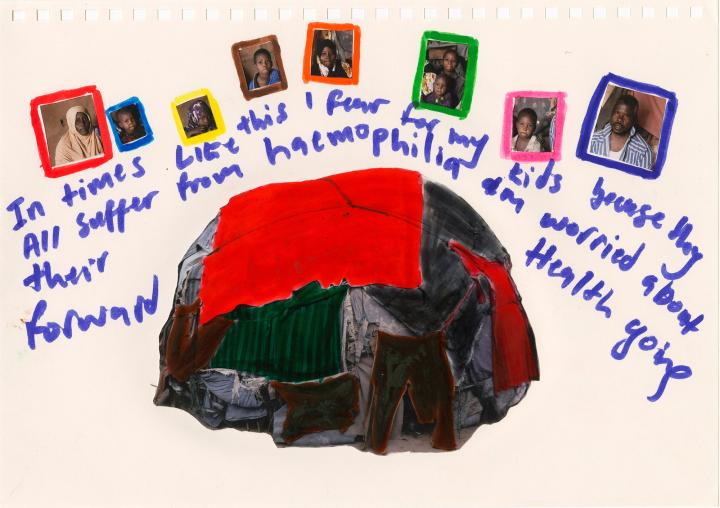

Sudan: Refugees at the border

These refugees from the Tigray region of Ethiopia fled across the border to reach Al-Shabat transit camp in Sudan’s Gedaref region. The Ethiopian government launched a military of-fensive in Tigray in November 2020, displacing more than 2 million people, according to the United Nations. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosIn November 2020, after a reported attack against a major Ethiopian army base, the Ethiopian prime minister ordered military action against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. Tensions had been building for weeks between the national government and people in the Tigray region, and the situation escalated into a military conflict. Thousands of people fled the violence, heading to other areas of the country or leaving to take refuge in Sudan.

Photographer Thomas Dworzak was on site in Sudan just weeks after people began to arrive. He described the extraordinary situation: “It presents a cynical parallel with the events of 40 years ago, which occurred in the same region and brought images, never before seen, of famine, deprivation, and horror into our homes. Today a large group of a people—the Tigrayans—are fleeing. This time, however, a collapsing communist regime is not responsible for their flight. Rather, it was ordered by a leader who is also a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.”

As people fled, some managed to bring their cattle and their belongings. Others, forced to depart in haste, left with empty arms and heavy hearts, leaving everything behind. Dworzak spoke with Salomon, a refugee who recounted his experience. “We didn’t expect war. But as soon as we learned what was happening, we fled to Sudan,” Salomon said. “We walked into the bush and stayed there for four days. We came here on foot. I left everything—my house, my store…. All I had was my telephone in my pocket.”

It took hours, and sometimes days, to reach neighbouring Sudan. As the families made their way, they travelled through a harsh and arid climate without access to drinking water, shelter or food.

Refugees from the Tigray region of Ethiopia wait at Al-Shabat transit camp. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosDuring the first weeks of the Tigray offensive, the MSF teams at the Sudanese border saw refugees streaming in. “When I arrived in mid-November, large numbers of people were arriving” recalled Hano Yagoub, MSF emergency coordinator on site.

"Every day, there were more and more people... Old people, children, babies, pregnant women—but especially young people, ages 15 to 25. … All they could think of was to flee to Sudan."

Once they had crossed the border, the refugees ended up in two main areas: Al-Shabat and Hamdayet transit camps. Living conditions were difficult at Al-Shabat, where shelter, food, drinking water, and sanitary facilities were scarce. Some families found refuge with local residents in the village who welcomed their neighbours from Ethiopia, while others had to sleep outside.

After several days of fleeing without food or water, the new comers finally reach the water point set up in the camp. The families wait patiently for their turn under a blazing sun.

To assist people living in the camp and provide them with medical care, the MSF teams set up a clinic, holding hundreds of consultations every day and assessing the refugees’ nutritional status. The most common diseases were respiratory infections, malaria, and other diarrhoeal illnesses. In addition to physical ailments, they also suffered from symptoms of severe psychological distress, such as anxiety and insomnia, reflecting the violence they had experienced in Ethiopia.

People receive medical care at an MSF clinic inside Al-Shabat transit center.

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosDestination Um Rakuba

Soon after arrival, these refugees were pressed to register for transfer to Um Rakuba camp in Gedaref state, one of the region’s official camps designated for people arriving from Ethiopia. Despite the lack of appropriate infrastructure and the fact that the numbers of arrivals exceeded Um Rakuba’s capacity, the growing use of threats—especially regarding food—and coercion drove refugees to register for placement in an official camp.

Ethiopian refugees prepare to board buses that will transfer them from Al-Shabat transit camp to Um Rakuba refugee camp. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum Photos"Whatever the arguments justifying these transfers, the refugees’ protection and their well-being must be the priority consideration."

A caravan of buses prepare for the hours-long journey to Um Rakuba refugee camp. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum Photos

A man kisses a woman’s hand as people board buses to Um Rakuba refugee camp. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosOnce registered, people climbed aboard the buses heading to Um Rakuba. After several hours, they arrived at the overcrowded camp that was already housing more than 20,000 people in rudimentary conditions. After being transferred here, the refugees were still exhausted and worried.

A child walks through an informal settlement near Um Rakuba camp. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosThe camp lacked the infrastructure to meet the needs of its residents, so MSF built hygiene facilities—latrines and water points—at multiple locations to prevent the spread of disease.

The World Food Programme distributed food to the refugees, both in the form of ready-to-eat meals and rations that people could prepare themselves. Some basic necessities, like jerrycans and cooking supplies, were also distributed, although there were not enough supplies for everyone. Trucks delivered drinking water, which was stored in large tanks at the camp. Families filled their jerrycans at the water points. To ensure sufficient water, the MSF teams provided logistical support, treating the water stored in the tanks, digging wells, and building pumping stations.

Holding umbrellas against the sun, people wait to receive food.

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosThe MSF teams set up a clinic where medical consultations were held. The facility had emergency, intensive care, and obstetrical units and hospital beds. The teams also handled transfers of the most critical cases to the Gedaref hospital.

A refugee family arrives at the MSF clinic in Al-Shabat transit camp.

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum Photos

To prevent and prepare for epidemics that could surge quickly in an overcrowded camp like Um Rakuba, the MSF teams carried out COVID-19 prevention activities. They also planned ahead for potential flare-ups of cholera, which is endemic in this region and particularly dangerous during the rainy season, when there is often heavy flooding. To limit the spread of infectious diseases, an isolation unit was set up in the camp clinic. These refugees have had high rates of chronic disease, including HIV, diabetes, and hypertension. Continuity of care is essential for these conditions, so MSF ensured that patients received medication and connected with national programmes in Sudan to facilitate long-term support.

A semblance of normality

This situation is not new. Large numbers of Ethiopian refugees entered the Gedaref region in the 1980s during the famine in their country and the ensuing humanitarian crisis. Now, more than 30 years later, the former refugee camps in the area have become communities, and the Ethiopians living there have integrated into Sudanese society.

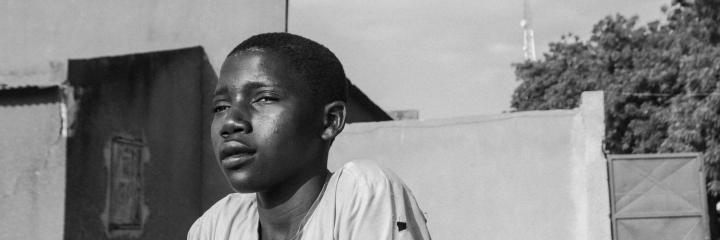

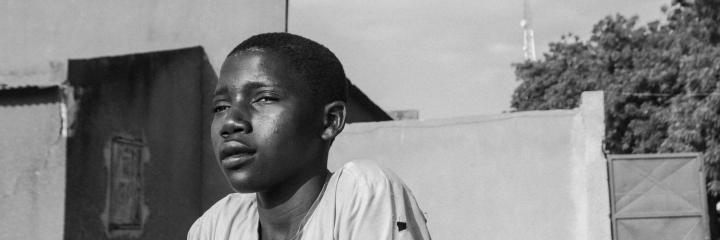

Today, all signs point to a situation that is likely to persist. The fighting appears to be far from over in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, and these refugees will probably not be able to return home for a long time. In spite of everything, music and laughter echo through the alleys of Um Rakuba. Sitting with Dworzak over a cup of coffee, Salomon gave words to his reality. “I have never experienced anything like this in my life,” he said. “My generation is too young to have known this. Even now, it’s hard to accept what is happening to us…. The most difficult thing is not knowing whether we’ll be able to go back to Ethiopia someday, to go back home.”

A woman shields her face against the dust in Um Rakuba camp.

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosLatest photo-reportages

Greece: Trapped in island camps by Enri Canaj, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack by Newsha Tavakolian, 2021

Mossoul, When The Birds Will Fly Again by Nanna Heitmann, 2021