Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road

Thousands of families have fled violence and insecurity in Honduras, travelling thousands of kilometres on foot, by train, or by bus, trying desperately to reach the United States. Many of them end up stranded in Mexico, often in very dangerous cities where they are targeted for kidnapping, assault, and extortion. Photographer Yael Martínez, who comes from Mexico’s Guerrero state, spent several weeks traveling with MSF between Mexico and Honduras, meeting people who are taking extreme risks to achieve their dream of a better life in a safe place. In his account below, he describes some of the MSF staff, patients, and other people he met along the way.

Coatzacoalcos, Mexico – Heading north

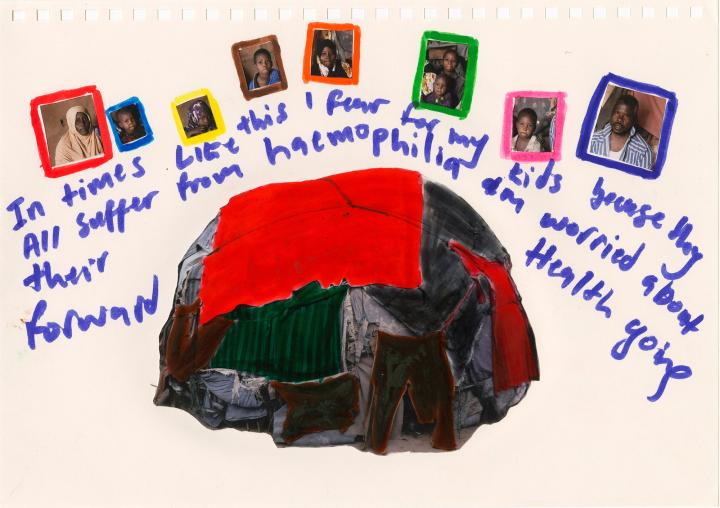

Karen Yoselyn Reyes, age 7, has been traveling for 12 days with her mother and little sister. After leaving Yoro, Honduras, they walked from Tapachula, in Mexico’s Chiapas state, to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz state. Karen is particularly worried that her mother will not be able to climb onto the train headed north because she is carrying Karen’s sister. Mexico 2021

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosThe noise was deafening. For a moment, I felt my heart beating fast in my left ear and a vibration going through my head and feet; it came up slowly from the ground until it was in my entire body. I saw how somebody threw a coin on the rail track, and I saw how Yahir—an eight-year-old boy from Honduras—bent down, grabbed the coin with a playful smile, and handed it to me. I touched what a few seconds earlier had been a 50-cent coin; it was still warm from colliding with the steel. I thought about what the pressure of the metal-to-metal collision can do—the pressure of life, of the inevitable, of what is sought, the pressure of big against small.

The image of a destroyed coin was the image of us trying to find ourselves. Of the violence we are, of the violence we experience, of the paths we have traced over the course of our lives.

More than 700 Central Americans take shelter under this bridge near the railroad tracks in Coatzacoalcos on the night of 23 March. Mexico 2021

© Yael Martínez / Magnum Photos

The Ramirez family waits under a bridge for the train heading to Monterrey. Mexico 2021

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosIt was getting dark, and yet another day was ending on the tracks. Darkness was upon us, and people gathered to make fires and protect each other from the night. The migrant shelter here in Coatzacoalcos had been closed for months due to the pandemic and the fear of COVID-19. Yahir and his father Wilson had been stranded here for weeks, waiting for a chance to get on the train safely. He and many other families—including women and children—were all waiting for the same thing, for the train to stop for a few seconds so they could all get on it safely. It was a long wait, and patience was slowly running out. That same day, a woman had fallen while trying to climb onto a moving train. The image of her falling in the air made everyone’s hearts pound out of their chests. Her screams were heard even amid the deafening noise of the train. Fortunately, her body did not fall near the tracks. She got up quickly and immediately started running towards the horizon along those tracks—no matter where they went, with only the certainty that those tracks were her guide.

The Zambrano family waits under a bridge on 24 March.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum Photos

I said goodbye to Yahir and the other children and went back to the hotel with Yeka an MSF communications officer. Before leaving, I went to the fire, to feel its heat, to feel close to the people there. Under this bridge, and by the train tracks, time runs differently. Time always runs differently in these spaces where dreams collide and where the voices of those who have left their land and their people come together.

The next morning, we left for Higueras, a community north of Coatzacoalcos, a small point on this journey north. We walked on the tracks. I stopped to talk with two men who were sleeping under a train carriage. Their feet had wounds from the journey, as they had walked most of the way. And suddenly one of them pointed to a carriage in the distance. There was a family making a video call to someone riding “La Bestia” [“The Beast” is what many people call the US-bound freight trains that migrants and asylum seekers often attempt to climb and ride north]. I walked towards them and climbed up onto the carriage. They came from Honduras, and they had been travelling for 12 days. The youngest of the group was seven-year-old Karen. She had a distinct look about her, as if she’d seen years go by in these last few days. The wind blew and made her hair dance, giving the scene a magical air as if her body barely touched the earth, as if she were floating above this piece of iron. I went up to her and took a photo. The carriage started to move, and we returned to the suffocating reality. It was a false alarm, just a train maneuver. Karen told the MSF doctor that she was worried about her mother and her sister, that she wanted to take care of them. She was scared that her mother would not be able to get on the train, and that they would be separated forever.

A father helps his daughter climb aboard the train in Coatzacoalcos on 25 March 2021.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum Photos

On my way back from the track I met Edgar and his family. They had been able to take the train in the morning, but they’d only reached Higueras. They were resting in a small house in ruins, traces of the fire they had made were still visible. They had been upbeat a few days ago, but their faces looked different now—with fear and uncertainty in their eyes. Edgar was looking at the horizon where the train was. The last time he tried to cross, he had gotten lost in the desert and they had walked aimlessly. He told me that he had started crying like a baby, thinking that it was all over, that his life would end in the middle of the desert. Border control officers found them—and that was, for him, a second chance at life, his salvation. He thought he would never try to cross again, yet here he is—again—looking for a new life in Texas.

![The countryside flies by the train that migrants call “La Bestia” [“The Beast”].](/images/38e10c60d6e1cc7b.jpg)

The countryside flies by the train that migrants call “La Bestia” [“The Beast”].

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosWhat makes this journey difficult is hushing yourself, making yourself invisible in the landscape, continuously leaving a bit of yourself behind like a piece of a jigsaw puzzle, so that later you look in the mirror and cannot find yourself, and you get lost in the tangled mess of time, dust, and cold.

Today is our last day on the tracks. We got here before dawn, and there are many people moving around, many more than at dusk. I met Ángel’s family and started talking with his father. He lived in Monterrey years ago, and that’s where they want to go. The youngest child is Mexican. She was born here and it’s her birthday today. Yeka goes into the store and returns with a Pingüino cupcake. The matches serve as candles, and all together we sing Las Mañanitas [Happy Birthday] to Deverlyn, who is turning two years old. Her father looks at her, sheds a tear, and smiles. The happy children eat a piece of cake and start to play. In the background, a green wall lights up, and Ángel starts to play with his shadow on the wall. This image makes me think that what divides us is our own shadow, our fears and projections of what we were and what we can be, of what we do not recognize, of the other.

Hours go by, and then it’s time to go. I say goodbye to everyone, and I see Ángel run towards me from afar. He gives me a big hug and says he will miss me. I get goosebumps and tell him to be strong and never stop dreaming, to think of this journey like a game, like a nightmare that’s about to end.

My guiding light takes me to the south, to his land, to our land, to try to understand why one leaves, why our children will no longer be from there.

Ángel Alexis Ramirez Mejia, 9, plays under the Coatzacoalcos bridge on 25 March. Since leaving Comayagua, Honduras, he and his family have been travelling for 16 days, 14 of them on foot.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosHonduras – Marked for life

The stories I have from Honduras are about families I met along the railroad tracks, families from Lloro, Comayagua, San Pedro, Zambrano, Santa Bárbara. They all said they had left nothing behind in these lands. That’s why they left; they had lost everything there.

The impact of the 2020 hurricanes, including the flooding, can still be seen in the village of Banderas on 8 April. Honduras 2021

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosFrom the sky it looks like a jungle paradise, lush with green vegetation. When I touch the ground it feels familiar, as if I were somewhere in Chiapas or on the Costa Chica of Guerrero [in Mexico]. Everything feels familiar, even the air in places that have been penetrated by violence. The Choloma neighborhood walls are almost identical to the ones in Las Cruces in Acapulco; both are marked by time, by dust, by the blood and sweat of men.

The 2020 hurricanes destroyed the neighbourhood of La Planeta in San Pedro Sula, Cortés region.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosWhen you walk, or move, your subconscious tells you that someone’s looking at you—and you are unable to see their face or say their name, or their names, like the forgotten gods, like the land that has been burned.

A survivor of sexual violence poses for a portrait in Choloma.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosY.M. was abused by her family since she was eight years old. It created such a void that she compulsively wanted to fill it with excess, with getting lost in herself, with getting lost on the streets. Her children gave her a reason to live, to fight, and to slowly shed the skin that carried all these emotions, the skin that’s been marked by family, that wants to learn to forgive and seek new horizons. The photograph she chose to represent herself shows her working in the fields. You can’t tell from the photograph, but she was pregnant. And in this moment she felt complete, with the strength to live and withstand anything.

N.V. sighs when she remembers her childhood, when she remembers how the protection of her space, her body, her soul was shattered. What it’s like to look into the eyes of the people you thought would protect you and to see in them the faces of your abusers. When you go through that, you lose the will to live, you feel guilt-ridden and dirty, she told us. But she left that behind and now she sees independence on the horizon. She chose an image with her daughter, her nurse, where she looked serene, luminous, filling the room with peace.

Lorena was very nervous, she wouldn’t stop tapping her right foot on the floor, and her breathing was heavy. Her voice started to break when she began telling her story, tears rolled down her cheek, and she went silent. When you listened to her breathing you noticed how she was shaking inside. Cecy handed her a tissue and took her hand. Lorena wiped away her tears and wrapped her left index finger with the moist tissue. At that moment, images were projected of the past, of the heat she had felt, of hunger, of destroyed landscapes, of desolate homes, of people struggling to find a safe place. All these images flickering in my head contrasted with the silence of the night, [punctuated by] the chirping of birds.

A.E.A., 34, a survivor of sexual violence stands inside her home in the Neuva Capital neighbourhood of Tegucigalpa.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosLorena’s voice slowly calmed down, and by the time we realized it, it was night. She told us about her safe space, about the place that made her feel calm. It was the sea, that place where she saw only moonlight and felt the sand on her feet.

She decided to record her story on her skin, to share what she had experienced through images. She had made symbols out of her life experiences. What I remember about her is an image of a dandelion. She told us about the fragility of the flower and yet its ability to bloom wherever the wind would take it.

Guerrero, Mexico – No exit

El Pescado village, in Guerrero state, Mexico, lacks electricity. Only the houses equipped with solar panels have access to power.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosIt took 12 hours to get to the village of El Pescado. It was a long journey full of dust, at times there was almost zero visibility and it felt as though you were entering a different world and time. To walk in the sierra, you need to know the area, and we learned this the hard way by taking a path on which we got lost for about two hours. We realized we were lost when the path came to an end. We had to go back and ask for directions to El Pescado. It was getting dark, and we still hadn’t arrived. We thought we would get there at around 5 pm—it was 8.20 pm. Yeka was nervous. Everyone in the truck knew that it wasn’t safe to drive on these roads at night. In these remote places, the state doesn’t exist. The community takes the law into its own hands; they create their own protection, and every person defends themselves from drug traffickers, from opposing cartels, from fights with others.

It is precisely because of this that we wanted to visit the community. A few months ago, an armed group attacked the people here and they were forced to move. The fight is for land, for the sawmills. Poppy has not been planted for a while.

We finally got there [to El Pescado] and put up our tents in the area where the school is. There is no electricity in the community, and that night the moon was beautiful. It lit up the sierra.

The community gave us handmade tortillas, black beans, rice, and chicken for dinner. It was a wonderful dinner after a long journey.

Maribel Mujica, 18, is at home with her two-year-old son, Gabriel, in El Pescado village in the region of Guerrero on 28 April. Mexico 2021

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosThe next day, people from the community started to arrive at the MSF site. They hadn’t received medical attention for months. You could feel the uncertainty in the place, in the faces of the people. The military, the national guard, and the state police were all over the place. You could feel how the apparent calm was about to vanish, the apparent calm in the state of Guerrero.

Homes in the small village of El Pescado have been abandoned because of widespread violence and organized crime in the state of Guerrero.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum Photos

Javier Hernandez is a community leader in El Pescado.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosWe waited before interviewing Javier [a local community leader]. He told us about the time armed men arrived and about the families who had to leave everything behind, about the difficulties they face here and the society’s distress. He told us that they had decided to stay and fight for what they have, to fight for their land and for their people.

Night was falling, and little by little people went back to their homes. It would take some of them an hour and a half by beast.

The doctors brought lamps that they used to light up the health center. Families waited for consultations, and these were given with whatever light they had. The image that lingers in my memory is of a mother with her daughters walking home in the dark. Their path was lit only with their cell phones, a path they would walk alone, at night. A path in those conditions takes you to the limit. It’s an act of faith.

The Arroyo family had to walk two hours in the dark to get back to their home. They had left because they feared organized crime.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosWe left El Pescado the next day, but before that we interviewed a family. They had left the community, they were threatened, and they were afraid. The wife agreed to talk to us. We were walking to a relative’s house, and on the way there she met another woman. She became very nervous. She told us that the entire community was being watched and that she didn’t feel safe. She changed her mind about being photographed, but agreed to give us a brief account. It was very short and choppy, her words didn’t flow; the silences and the texture of her voice were full of fear, of uncertainty about her life and that of her family.

In the afternoon we moved to the community of El Durazno. There was a moment of tension when we saw a group of armed people coming towards us. They all had long guns and automatic weapons. Pau [an MSF staff] went up to them. They were upset because they thought we had taken supplies to El Pescado; they were in conflict with that community.

It was a tense moment, but Pau told them they could jump in our vans and see what we had. They let us go, and after a few minutes one of the authorities of the community arrived and apologized for the way we were treated. We finally went to eat, and we interviewed him later that afternoon. He told us about the context, the need to grow crops, why they defend their land, and why there are conflicts. Pau asked about the solution to the problems, and one of the armed men started talking. “Conflict is inevitable, and we hope it comes sooner rather than later.” Night fell and wind blew over the pine trees. Mist hugged the mountain, and the air felt tense.

The next day we left the sierra for Zihuatanejo. Those were long days that felt strange, filled with an uncertainty that was about to be broken, with a light sleep that brought you closer to the earth, to feeling vulnerable, to feeling like water spilling from your hands.

Amairani Mujica, 7, wipes her eyes at home in El Pescado on 28 April. Because of organized crime, the families in this village lack medical services, security, and the opportunity for economic development. Many have been forcibly displaced.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosI received a message from Yeka a few days ago. It was a video of women crying, asking for help from the authorities. The women who had received medical attention in those days [when we visited El Pescado] were now in the same health center crying for their lives, for their children’s lives. You could hear shots in the distance, you could feel how the rooms were filled with fear, how the voices broke. These were voices from another time, of girls, boys, women, mothers, grandmothers. They all became one voice, a single image with a beating heart. These lands are being abandoned, dismembered, uprooted, infertile.

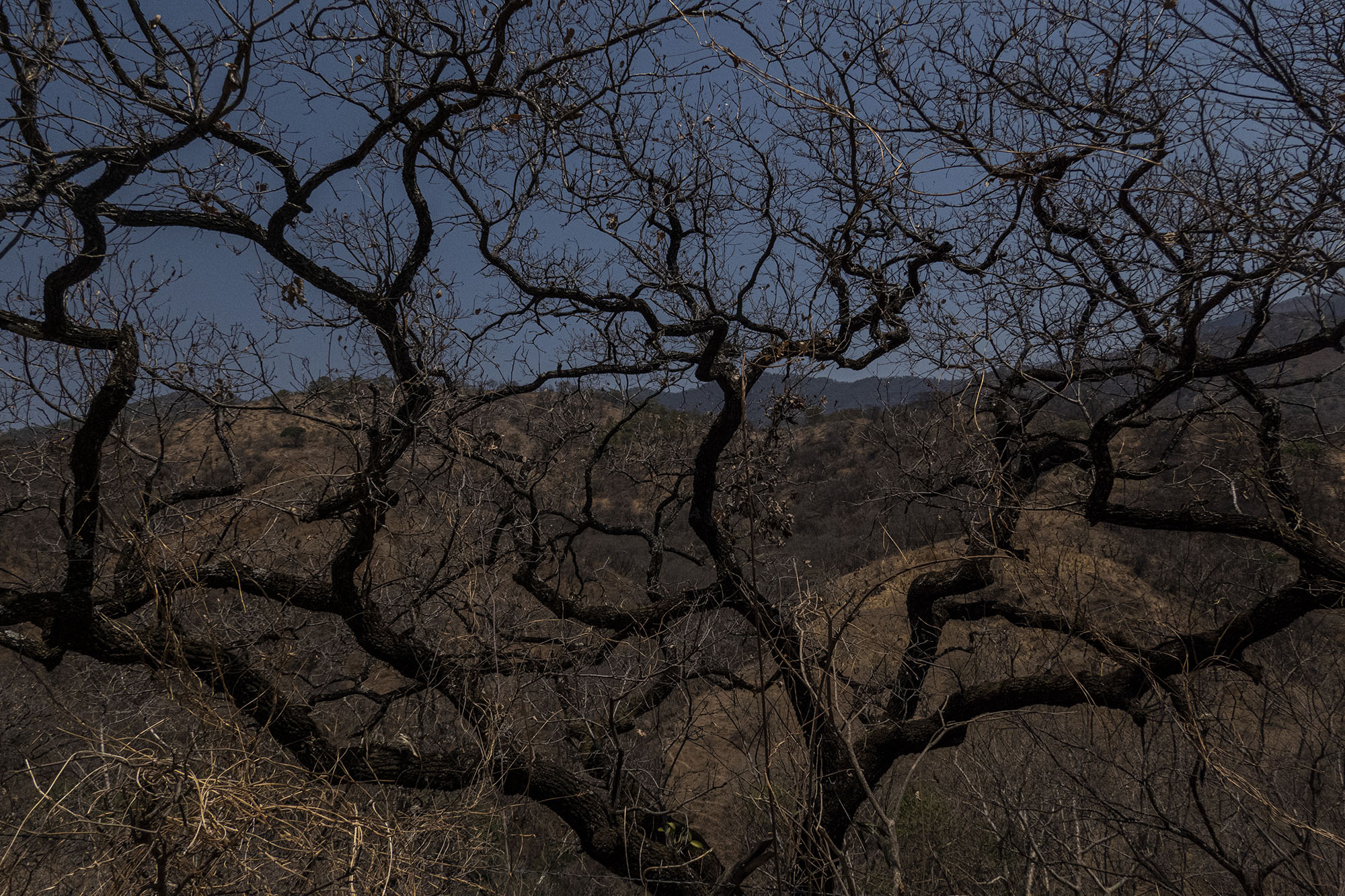

Organized criminal groups want to seize the forests in order to control logging, one of the ways in which people have been forcibly displaced from these lands.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosThat smell of dust, of earth, was the same as in Choloma, in Coatzacoalcos. It’s the smell of the men of our days, of our times.

Tamaulipas, Mexico – Blood on the road

I’ve always thought that border cities are violent, the forces of nature clashing against men, against our way of thinking and understanding life, man clashing against man, and against what we define as reality.

Tamaulipas has all these visible marks—in its geography, in its space, in the spirituality of its people. Here, dreams don't just bounce off, they burn, they bleed out.

Space seems to be silenced, stunned, contained by the voices of lament.

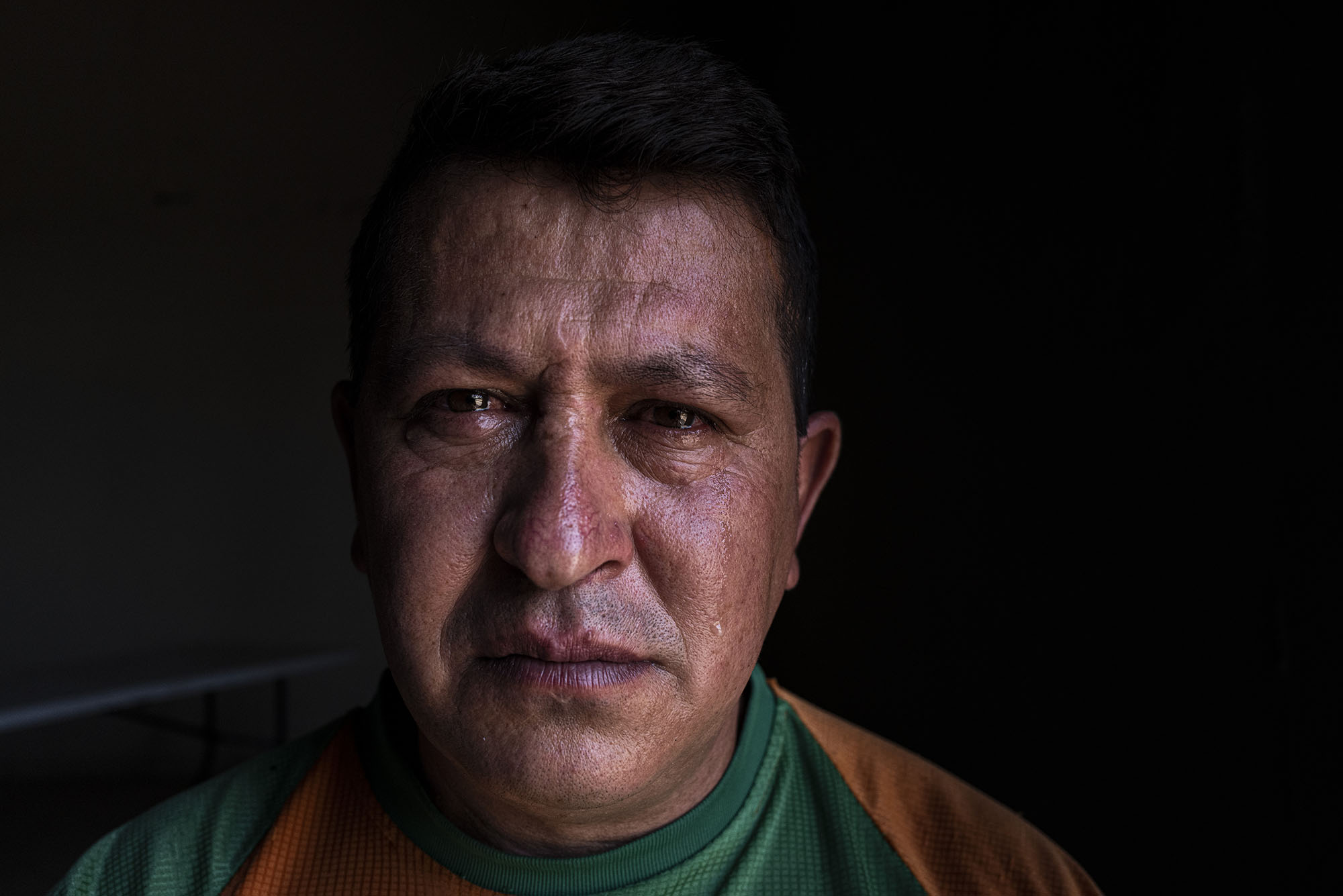

It’s our first day [in Reynosa] and we went to a shelter with Sergio [an MSF communications officer]. We spoke with a Honduran family who fled their country for fear of being killed by their own blood, by their own family. The woman cannot hold back her tears and hugs her husband. She no longer recognizes herself—she and her family are not the same as when they left Honduras. Time and reality have changed them, their experiences have changed them. I got goosebumps from seeing them hug, from seeing them look at each other. They’re not like when they left Honduras, they’re not the same as yesterday. But this terrible reality has also kept them afloat, together, and they have become more connected.

Cindy Caceres, 28, and Carlos Roberto Tunez, 27, from Honduras, are staying in Reynosa while seeking political asylum in the US.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosIt’s another day, and today we met a transnational family: a Haitian father, a Honduran mother, and the youngest child is Mexican. They met in Chiapas and the road has brought them here to northern Mexico. When we got to the neighbourhood, a Mexican woman with a hostile attitude asked me why I was taking pictures. I explained the work we were doing, and we entered the house. She came in an hour later and her demeanor had changed. She began threatening and insulting us so that we would leave. The house was big, and several Haitian families shared it. That part of the neighbourhood was controlled by drug traffickers.

We left the house, and the state’s abandonment became more apparent to me. The next day we arrived before dawn at the camp in Reynosa, this ever-growing camp where by now around 500 people have been counted. All of them are waiting for an opportunity with a tiny glimmer of hope. The people who had tried to cross the day before were on the stairs of a pavilion. Their clothes were dirty and still wet, their shoes full of mud. They were exhausted—physically and mentally. I tried to talk to them, but I couldn't photograph them. My memories were coming back, my body memory was loaded, and my muscles felt tense. I couldn’t fall asleep

People from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico are crowded together in a new encampment in the centre of Reynosa.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosWe heard heartbreaking accounts, where history repeats itself, where the persecutors seem to be the same, where someone stabbing someone else is the reflection of ourselves, of our deepest dreams or fears.

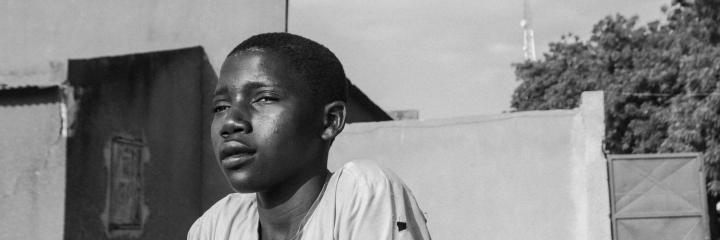

Freddy Alberto Pabon, 49, left Venezuela after his mother and brother died. He is seeking political asylum in the US for himself and his remaining family members.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosNo one can live on this land anymore, it has been burned by our ambitions, by our dark desires.

I left Tamaulipas with an image of death, of danger—of seeing a woman being run over by a man, and, instead of helping her, he wanted to get her out of the way, to go around her, to throw her on the sidewalk as if she were an object.

Luisa Coto, 33, left her country after receiving death threats and losing two family members. She now lives in an encampment in Reynosa.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum PhotosI remember we were told that at night some women and children disappeared in the camp, before everyone’s eyes, before everyone’s fear.

The image of the woman [hit by a passerby in Tamaulipas] was still in my head, with the lost, absent look on her face, as if she were dead. That image completely soaked me like her blood on the pavement.

This has been only one journey, for the resilience humankind, for the fight for what we call life, for all voices uniting, and for the song of our existence to burn eternally.

The Rio Grande flows through Matamoros.

© Yael Martínez / Magnum Photos