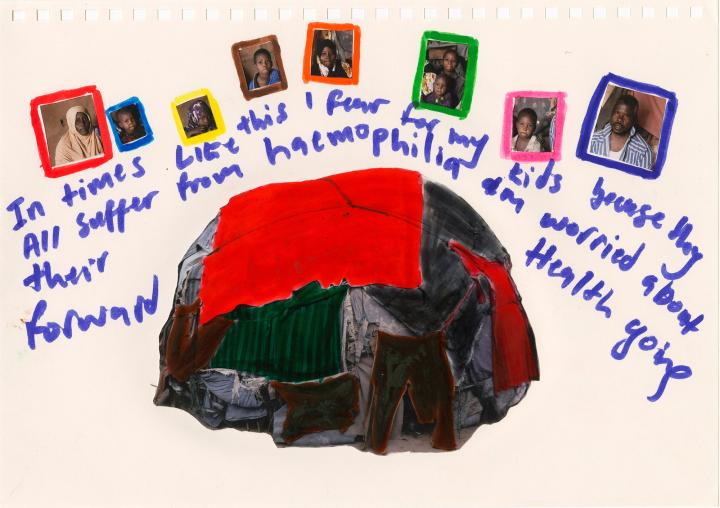

Whether internally displaced or refugees—these people must flee to survive

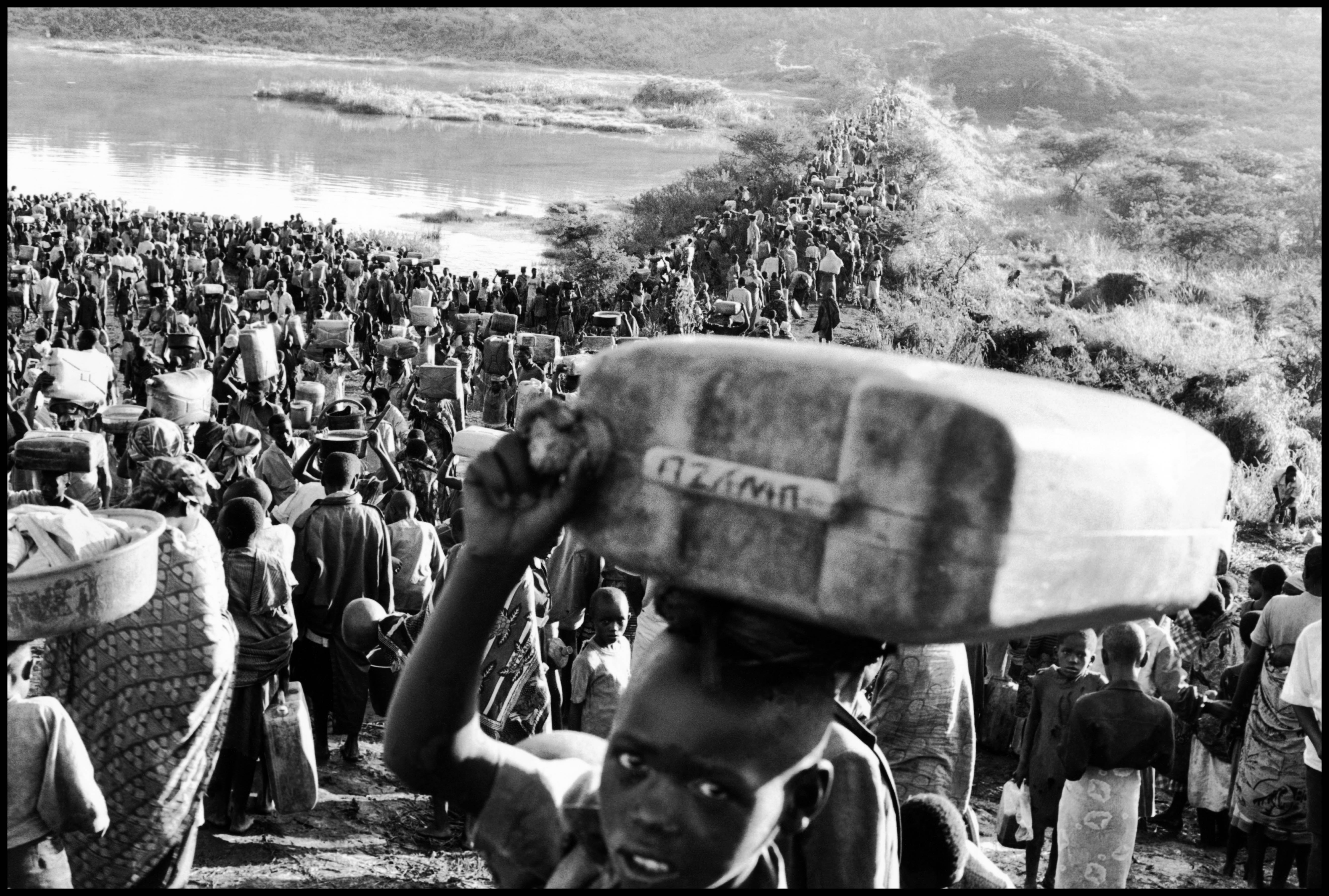

Rwandan refugees move through Ngara camp in Tanzania, near the border with their home country. Tanzania 1994

© Gilles Peress/ Magnum PhotosWhen violence breaks out, the instinct to survive drives people to flee to neighbouring regions or countries. However, the places where they take refuge are not always prepared to welcome large numbers of new arrivals, so everyone must work quickly to organize life in informal camps. If humanitarian workers are not already on site, they arrive in the early days of the emergency, as do photographers. While living conditions are difficult and restrictive, the key is to preserve or restore the dignity of the individuals who find themselves held hostage in a situation beyond their control.

Finding refuge in the camps

Fleeing a crisis situation means, first, leaving everything behind. Once people reach a safer place, their survival needs must be met immediately—building shelters and providing access to food, water, and basic hygiene services. For people in the midst of chaos and pain, having lost everything, health workers and humanitarian staff can offer a glimmer of hope. Over time, daily life and mutual support help to restore a certain normality, which the photographer’s lens captures.

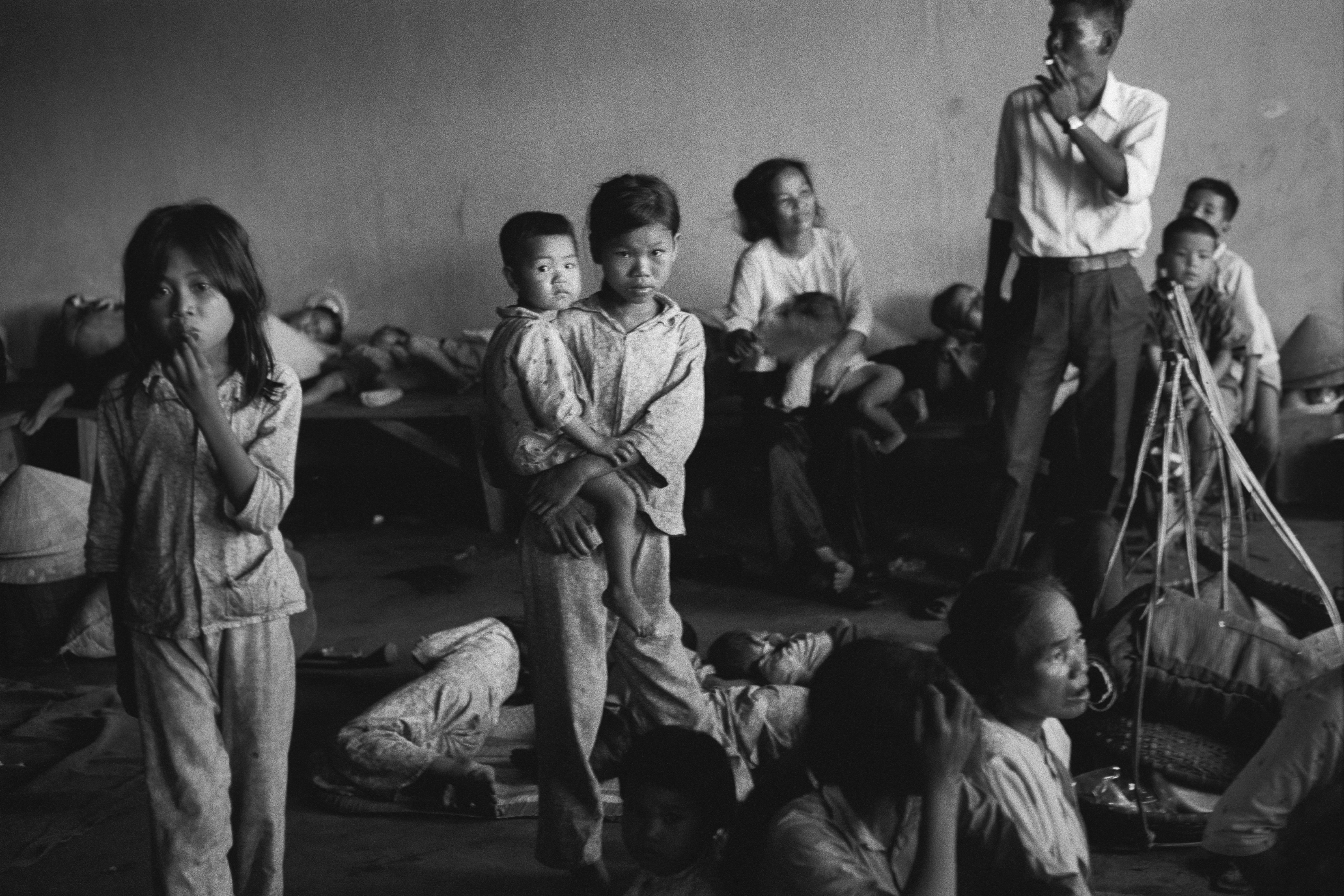

Cambodia 1975

© Hiroji Kubota / Magnum PhotosIn the 1970s, oppressive regimes in Cambodia and Vietnam drove one million people to flee to neighbouring Thailand. This was MSF’s first experience working in refugee camps. Under the auspices of other NGOs, MSF staff worked in the Aranyaprathet and Ban-Vinaï camps and, later, the informal Nam Yao and Chieng-Kong encampments. After several years, the latter two became official camps. Doctors were sent to those locations where many refugees were settling, often without water or sanitation, in extremely crowded conditions.

In 1976, Claude Malhuret was working in the Aranyaprathet camp, which housed 7,000 refugees. “No one really knew much about refugee camps,” he said. “There was no body of medical doctrine on this topic, no literature, and no definition to rely on. I saw these men, women, and their children. As I listened to them, little by little I came to understand the extent of the horror that had played out there under the Khmer Rouge. These were people who’d been hunted down. Their faces were haggard and their limbs were swollen by beriberi [vitamin B1 deficiency]. You had to drag the words out of them. Most were terrorized. They collapsed, sobbing, at the least question.”

Thaïland, 1980

© Steve McCurry/ Magnum PhotosFacing a lack of supplies and staff in the camps in Thailand and wanting to meet the refugees’ needs, MSF realized that a solid, organized structure was required, backed by a logistics system. Starting in 1977, when he returned from Thailand, Malhuret emphasized that point. “The world of today and tomorrow will be a world of refugees,” he said. “MSF must provide its workers with the resources they need to deal effectively with this new reality.” Led by pharmacist Jacques Pinel, MSF created a logistics structure there in the Sakéo and Khao I Dang camps.

Working alongside the refugees, MSF staff tried to reorganize life in the camps. Many refugees played an active role, becoming nurses, nursing aides, and orderlies. “They oversaw the health services, registered new patients, and referred the most seriously ill to the hospital,” explained Esméralda Luciolli, an MSF doctor who worked in the Surin refugee camp in 1979. “These ‘guardians of hygiene’ succeeded, organizing teams to collect garbage and teaching women to boil water and children to use the latrines.”

Yves Coyette, an MSF doctor, treats a sick baby in Khao I Dang refugee camp. Thailand 1984

© Burt Glinn / Magnum PhotosRony Brauman’s first assignment was also in the Thai camps. In October 1979 he arrived in Ta Prik, at Cambodia’s northern border, which 30,000 refugees had just crossed. “We showed up to witness the most terrifying event I’d ever seen in my life,” he said. “Tens of thousands of motionless people collapsed one on top of the other, a dark, compact mass of people, huddled together in this corner of the savanna. Not a noise, not a single word, not even an infant crying. Just wheezing sounds, coughing fits, the rustling of the wind, the stifled cries of animals in the distance.”

Only the survivors had arrived because it was still impossible for aid workers to cross the border. Aid could not enter Cambodia. As a result, some of the staff had to be able to provide assistance as close as possible to where the needs were—rather than remain at the periphery. Thus, in February 1980, MSF held a symbolic march at the border bridge between Thailand and Cambodia, together with international media and other NGOs.

They called for food convoys to be allowed to enter the country. Malhuret spoke before cameras from all over the world. “At this moment, 500,000 Cambodian refugees, 500,000 civilians massed along the border, could—from one day to the next—be turned back to face soldiers shooting at them. We are here to demand protection for these civilian lives, the lives of unarmed people. We beg you, at this moment, you, the soldiers before us now, to allow these trucks carrying food and medicine, the teams of doctors who ask only for the simple right to aid the survivors of a long, too-long, tragedy, to enter Cambodian territory. Seated a few metres away, our delegation, representing millions and millions of people shocked by what they sense is happening on the other side of this border, are willing to wait all day for your response and authorization.”

To no one’s surprise, the regime turned them back. Despite that failure, significant media coverage helped to awaken the public to the refugees’ plight.

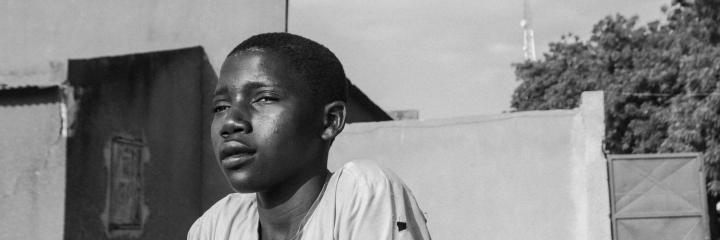

Several years later, in 1994 and, subsequently, in 1996, violence rocked central Africa, far from the cameras and the world’s television screens. To film the documentary, Afriques: comment ça va la douleur? [Africa, How Are You with Pain?], photographer Raymond Depardon spent five months crisscrossing the continent from the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa, to Alexandria, Egypt. The title refers to a phrase that Chadian revolutionaries used to shout out during his long stay there. The word ‘pain’ is used lightly here, as part and parcel of daily life. The images he shot are accompanied by short written texts read by the filmmaker himself. The texts are not commentary, but they capture how he looks at and understands each context. During his journey, Depardon met MSF teams in Burundi, which was being torn apart by civil war. He photographed displaced families living in tents and those who lacked access to vital supplies. MSF was working in the camps, treating malnutrition and diseases caused by unhealthy living conditions and inadequate food. The organization also supported referral hospitals in the different provinces.

Even in the midst of the most tragic situations, Depardon chooses to let the images speak for themselves. “I don’t travel the world, I don’t take photographs for that,” he says. “I’ve managed to take a few strong pictures, but I work just like everyone else. Sometimes I’m horrified, but sometimes what I see challenges preconceived notions I might have: good people on one side, bad on the other. You have to be careful. And sometimes, you’ve just got to sit back; photos can also redirect us a little.”

Human dignity is at the heart of the photographer’s work.

Chartered buses transport Kurdish refugees from northeastern Syria to Bardarash camp in Dohuk province, Iraqi Kurdistan. This photo was taken at the Sahela border post. Iraq 2019

© Moises Saman/ Magnum PhotosOffensives and other outbursts of violence continue to push people to flee. More recently, in 2019, the Turkish army bombed the Syrian Kurdish enclave of Rojava, located on the Turkish border in northeastern Syria. As a result, more than 12,000 refugees arrived in Iraqi Kurdistan.

“Immediately after fighting began in northeastern Syria, we made a rapid assessment of the entry points at the border between Iraq and Syria, including reception sites and camps where the refugees would be received,” explained Marius Martinelli, MSF project coordinator at Bardarash, the camp where the refugees settled. Photographer Moises Saman was also there from the start.

Mental health care was the refugees’ most urgent need. “Starting from the first day, most of the people screened by our mental health care team showed signs of anxiety and depression,” said Bruno Pradal, MSF mental health manager.

Mobile teams composed of health workers from the region visited the tents to meet families, identify symptoms, and provide initial psychological support. Jamal and Jalal, both MSF community health workers and interpreters, had the painful experience of refugee life when the Islamic State occupied their region in 2014. “We fled to the mountains,” Jalal said. “Then, with some of my relatives, we crossed the Syrian border before heading to Dohuk, in Iraqi Kurdistan.” Jamal added, “As former refugees, we know what these people are feeling because we’ve had similar experiences. My work today is to visit the tents to meet the families and identify symptoms of psychological trauma so that they can receive treatment.” In the midst of tents, and surrounded by hills, photographer Moises Saman recorded the moments of freedom that the children in the camp sought.

Children play soccer in Bardarash camp. Iraq 2019

© Moises Saman/ Magnum PhotosWhile one might assume that refugees would find some measure of safety in a camp, that’s not always a given. Working with displaced people and refugees requires adapting to the constraints—formal and informal—imposed by the authorities. When conditions are no longer acceptable, you have to leave.

The limits of assistance

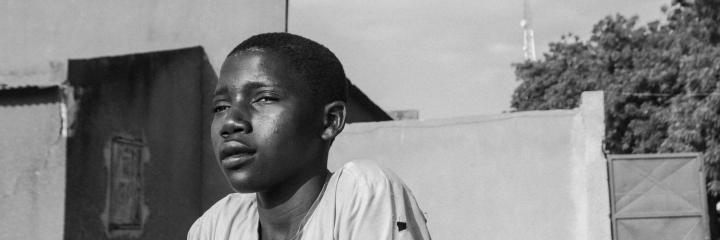

A child looks straight at the photographer documenting conditions inside a Rwandan refugee camp in the Ngara region of Tanzania, near the Rwandan border. Tanzania 1994

© Gilles Peress / Magnum PhotosOn 6 April 1994, the airplane carrying the Rwandan president was shot down as it approached Kigali. The slaughter of the Tutsi minority began in the days that followed. Between April and June 1994, between 500,000 and one million Tutsis were victims of systematic extermination. This genocide was the outcome of longstanding strategies implemented by political-military extremists who roused ethnic resentments against the Tutsi minority. During that period, the same extremists also killed many Rwandan Hutus who opposed the massacres. On 13 April 1994, an MSF team composed of five experienced staff, including Jean-Hervé Bradol, arrived in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, to support the team that had been there since 1993. Bradol described his disbelief upon arriving. “There were more dead than wounded,” he said. “But the weapons used—machetes—could not be considered weapons of mass destruction. The systematic killing of Tutsis and Hutus suspected of failing to support the killers ultimately convinced us that only overwhelming political determination could produce this result.”

A pile of machetes in Goma, near the Rwandan border. Zaire 1994

© Gilles Peress / Magnum PhotosAfter documenting the horrors of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, Magnum photographer Gilles Peress went to Rwanda during the genocide. “The immensity of this crime is beyond our imagination and is surpassed only by the unbelievable indifference of the West and the developed nations who would have been able to intervene and prevent the crime.” For that reason, he titled his 1995 book The Silence, referring to the silence of the international community. The book is a collection of the work he produced there. Journalist Philip Gourevitch was a special envoy to Rwanda for The Paris Review. Speaking about Peress’ photographs, he wrote, “What you see here, in Gilles’s photographs, exists only because he photographed it and because you’re looking at it. Everything that was then, remains only as memory. That’s life, and life—voices. Rwanda is full of voices and the voices are full of memory.”

A man with a terribly wounded face looks into the camera at a hospital near a camp in Kabgayi. Rwanda 1994

© Gilles Peress / Magnum PhotosInternational staff in Rwanda could not protect locally hired staff and patients, whom they knew to be in danger, from the massacre. When the mission was evacuated to neighbouring Burundi, Rwandan staff were turned back at the border. Returning to Paris, Jean-Hervé Bradol, MSF programme manager for Rwanda, recounted the atrocities that were taking place. MSF decided to speak out. The organization held a press conference and its statement was published in the 18 June 1994 edition of the French newspaper Le Monde. “We are direct witnesses to this today,” it read. “The lists of people to be killed were prepared with the utmost care and distributed on the first day. People were killed on command, ‘cleansing’ was conducted house-by-house. We know who the perpetrators of these massacres are: members of militias led by the dead dictator’s entourage. After the UN Secretary General acknowledged that a genocide was underway, so did the UN Security Council. Today, words that fail to lead to action are obscene. Genocide demands a radical, immediate response. The response so far can only be considered first aid. But doctors don’t stop genocide!” After intense internal debates on the decision to break with the principle of humanitarian neutrality, MSF called for an armed international intervention. The French Army’s Operation Turquoise would save lives, but also facilitated the escape of Rwandan armed forces into Zaire.

Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans fled at the same time, under threat and the influence of official propaganda and out of fear of abuse by the militias. They ended up in camps in Tanzania and Zaire. Humanitarian workers were there to offer care.

During the summer of 1994, MSF organized a response to fight cholera among the refugees in Zaire. But once the epidemic was under control, staff faced the [former Rwandan military] leaders’ brutal grip over the people living in the camps. Some of those sites were transformed into rear bases to take back Rwanda. Huge amounts of aid were hijacked, and the refugees experienced threats and abuse.

The humanitarian workers were outraged by the situation, but divided on how to address it. Some thought that MSF should end its activities in the camps. Others believed that they still had an opportunity to improve the situation, while still others wanted MSF to remain as long as the refugees needed aid, regardless of the circumstances. In November 1994, the NGOs working in the camps in Kivu, Zaire, called on the UN Security Council to deploy an international police force to separate the refugees from those responsible for the genocide. There was no response. At that point, as it worked to develop a common response, the MSF movement faced the following problem: should it continue to work in the camps, thereby strengthening the génocidaires’ control over the people there, or withdraw, renouncing its commitment to assist people in distress? With the emergency phase over, and because the situation did not improve, the organisation decided to stop working there and left the camps between 1994 and 1995.

Rwandan refugees move through a camp in the Ngara region of Tanzania, near the Rwandan border. Tanzania 1994

© Gilles Peress / Magnum PhotosLeaving space, listening, and trying to understand the complexities

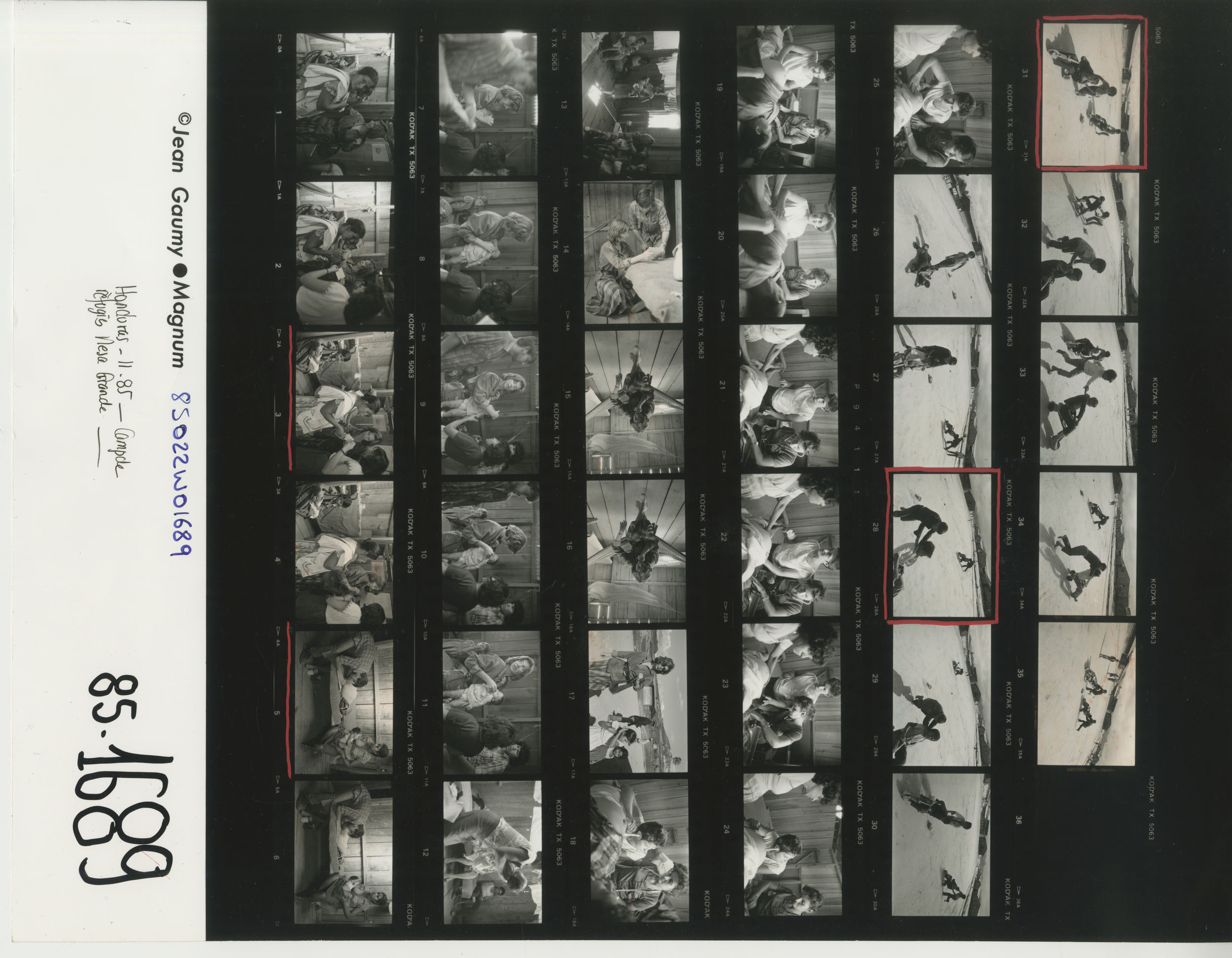

A contact sheet of Jean Gaumy’s photographs show refugees and MSF staff in Mesa Grande camp. Honduras 1985

© Jean Gaumy / Magnum PhotosDuring the 1980s, Central America, particularly the countries of Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, experienced intense conflicts. Guerrilla fighters opposed authoritarian governments, which led to civil war. Those who were not trapped fled to neighbouring countries, moving to huge informal camps or living with host communities. More than 15,000 Salvadoran refugees were massed along the entire 200-kilometre [124-mile]-long border between El Salvador and Honduras. In July 1980, MSF began working in the Mesa Grande camp in Honduras, located approximately 50 kilometres [31 miles] from the border. This MSF team, composed of three doctors and two nurses, first organized mobile clinics in the surrounding villages, where the refugees, traumatized by their experience in El Salvador, were hiding. At the health centre, the team treated diseases caused by disastrous living conditions. The facility later became a small four-room hospital, which included a maternity ward.

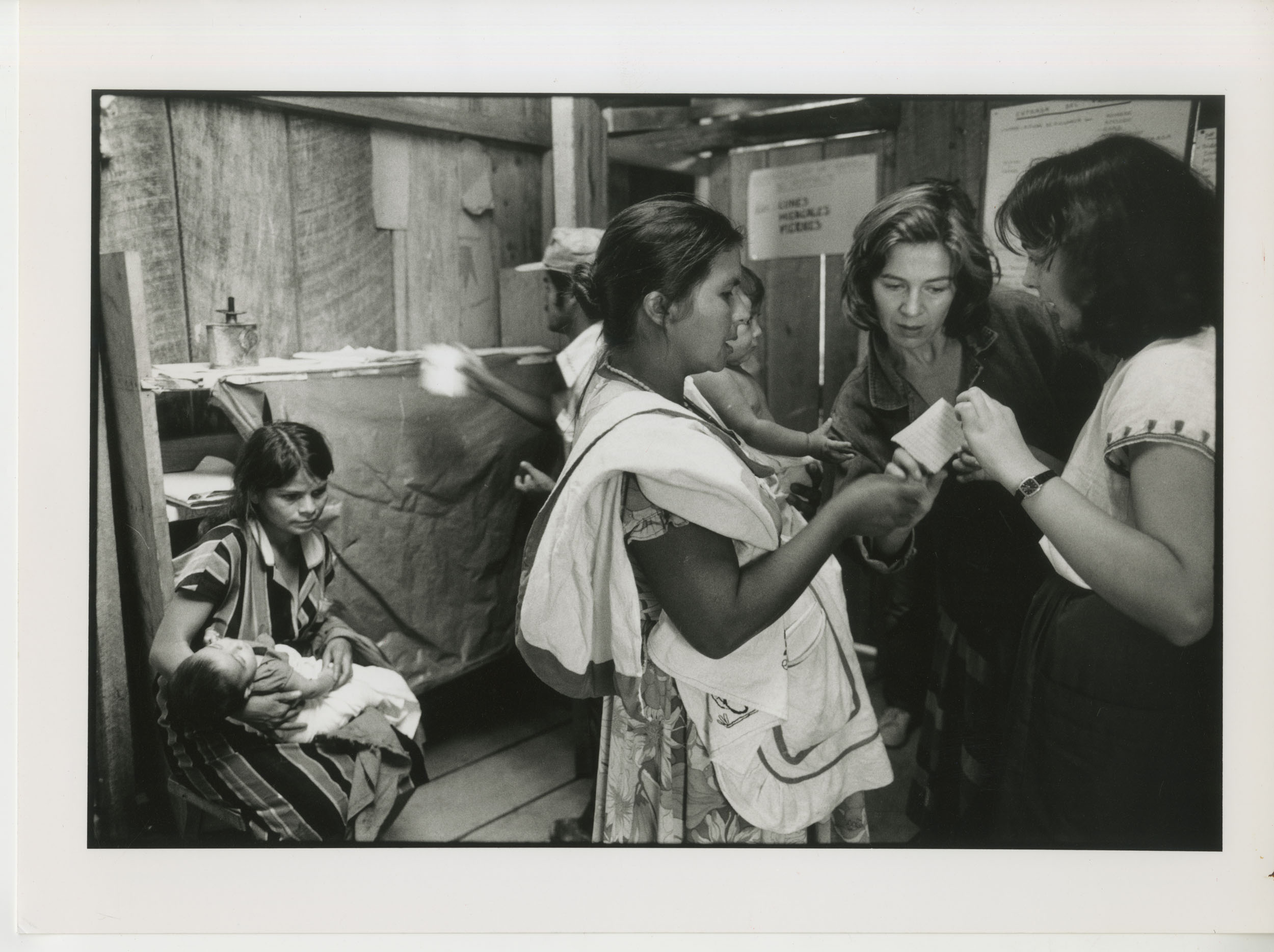

MSF staff work inside Mesa Grande refugee camp. Honduras 1985

© Jean Gaumy / Magnum Photos

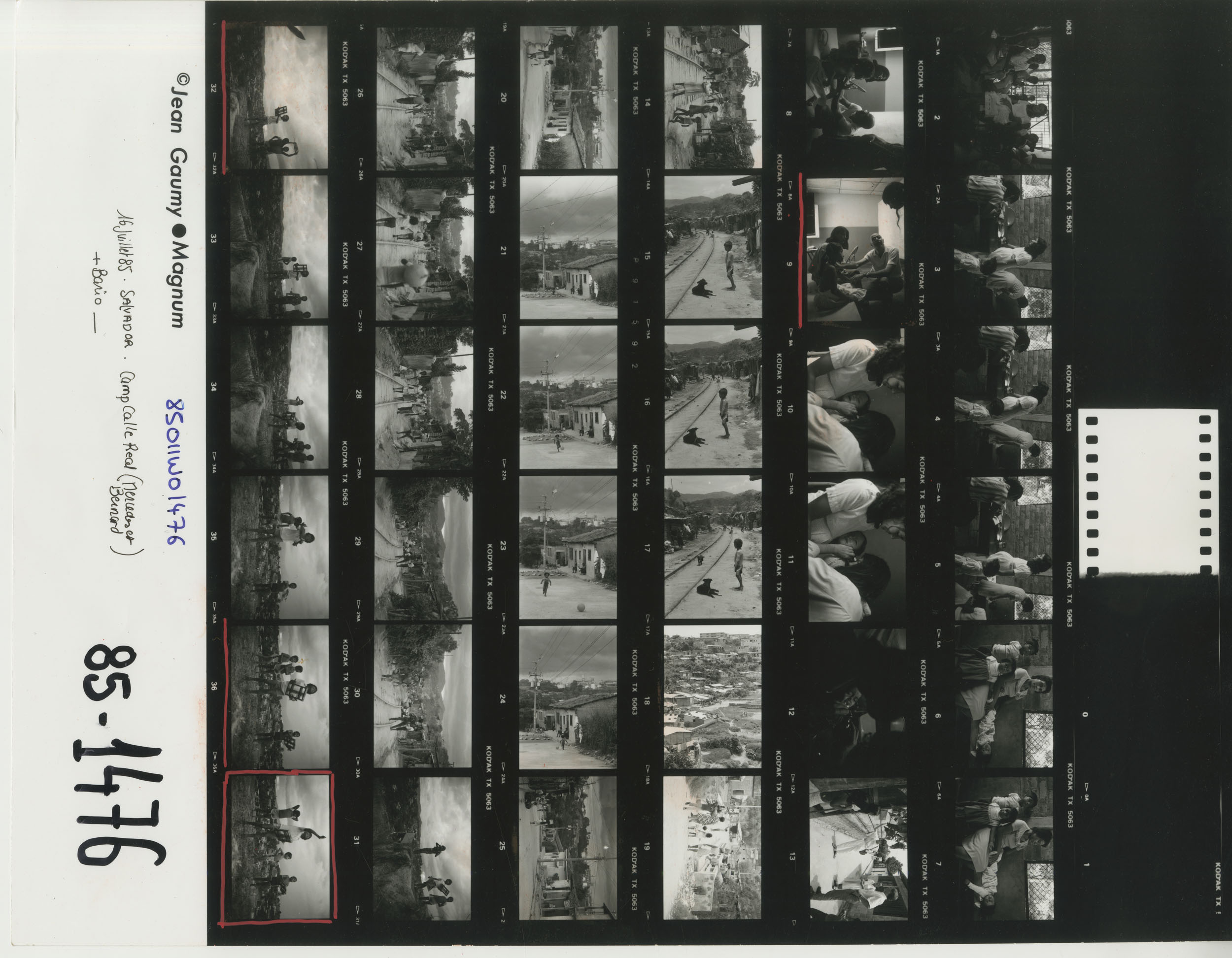

A contact sheet of Jean Gaumy’s photographs show refugees and MSF staff in Calle Real camp. Honduras 1985

© Jean Gaumy / Magnum PhotosIn 1984, Xavier Emmanuelli, MSF’s departing president, visited the projects in Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala. He brought a journalist, Claude Mauriac, and a young photographer, Jean Gaumy, from the Magnum agency. Emmanuelli wanted the perspective of someone outside of MSF at that time. Nearly 40 years later, he remains convinced that the photographer’s narration was important because only subjective images can convey the human dimension of the humanitarian mission. “Jean Gaumy understood that!” he said. “Once he finished his assignment with us, he went back, paying his own way, to complete the work he’d started. Jean had his own visual narrative, images that captured a universal moment. Whatever happened and wherever it happened, we see the codes of human behaviour in his photos. That’s because Jean feels affection for the people he photographs. His outlook on the world is engaged, committed.”

Children play inside Mesa Grande refugee camp. Honduras 1985

© Jean Gaumy / Magnum PhotosGaumy remembers how important this work was to his career. “This trip was an initiation,” he said. “I discovered things. I met MSF staff who explained what was going on there. Their stories spoke to the courage of their choices. Every assignment changed us. Both photographers and humanitarian workers—in the face of the reality of the crises that we see, we’re nothing, we’re overwhelmed. And that’s what brings us back to a kind of humanity.”

An Albanian Kosovar woman holds a child. Kosovo 1999

© Cristina Garcia Rodero / Magnum PhotosSeveral years later, in 1999, as abuses continued against Albanians in Kosovo, photographer Cristina Garcia Rodero travelled to be with Kosovar refugees and displaced people. “When I heard that the Albanian Kosovars had been expelled from their country I was in Mexico, but I went there immediately,” she says. “I knew where Skopje was and where the border was and I went there. Then I had to get to the refugee camps and talk to people.”

Albanian Kosovar refugees gather. Albania 1999

© Cristina Garcia Rodero / Magnum PhotosHumanitarian aid workers were also in Kosovo. Keith Ursel, MSF’s emergency coordinator in Kosovo in 1998, warned about the difficulty of operating there and the critical situation facing the displaced people. “These people are suffering terribly,” he said. “Not only are there no medicines to help them, but now even those who care for them are being targeted. Winter is coming and temperatures are falling to dangerous levels in Kosovo. Approximately 200,000 people have been displaced. Thousands of them are living in the forest with very little aid.”

After negotiations to end the war in Kosovo failed, NATO launched Operation Allied Forces. Air strikes began. MSF evacuated the country, but continued to work in refugee camps in Albania, Macedonia, and Montenegro.

In a 1 April 1999 press release, the organization announced, “This morning, a DC-8 plane left Ostend for Tirana and another aircraft left Amsterdam for Skopje, Macedonia. They are carrying 50 tons of medical equipment and supplies, blankets, tents and plastic sheeting, water storage containers, and pumps. Four staff were on the plane to Skopje and three in the one headed to Tirana. They will support the teams already on site.“

Children comfort their injured friend in Stenkovac refugee camp. Macedonia 1999

© Cristina Garcia Rodero / Magnum Photos“The children were playing, which shows human beings’ capacity to adapt to the terrible circumstances they’re living in,” Rodero said. “They followed me, wanting to play. They followed me wherever I went, to tease me. The little boy got hurt—you can see the children comforting him in the photo. His friends were very young too, and when they stuck their arms out of the window to wave to me, the youngest hurt himself. The others were so tender towards him, comforting him because he started to cry.” Through this assignment, which left a strong impression on her, she came to understand the meaning of the photographer’s work in more specific terms. “You have to share and want to tell stories. It’s knowing what you want to say, where you want to go and why you’re going there. What are you going to do with your work? What is your mission? What’s your goal? And you’ve got to search, search patiently. If you don’t find what you’re looking for, you have to come back the next year and then the next. And you can’t let yourself get discouraged. That’s when things happen that you could never even imagine.”

Since August 2017, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people, victims of violence, have fled Myanmar for neighbouring Bangladesh. “Before reaching land,” Saman explained, “most refugees disembarked on the shallow muddy shores and then proceeded to wade through vegetation carrying the few belongings that they were able to take with them.”

A 49-year-old father told MSF, “I fled my house with my family, but my son was shot as he ran. I took him to the hospital here in Bangladesh, but I had to leave the rest of my family in a forest in Myanmar without shelter, just hiding. I haven’t heard from them for days. I don’t know what to do. I’m really desperate.”

Most of the families settled in makeshift camps in Cox’s Bazar without shelter, food, drinking water, or latrines. The medical facilities that MSF and other organisations set up on an emergency basis were quickly overwhelmed. Konstantin Hanke, an MSF doctor, was there. “Five hundred fifteen thousand [refugees] might seem like an abstract number, but as a doctor here, you see what that actually means,” he said. “A tiny bit more bad luck, and we’ll have an epidemic on our hands.”

A Rohingya refugee sits with her sick child in the MSF clinic in Kutupalong camp. Bangladesh 2017

© Moises Saman / Magnum PhotosAfter visiting the camp in Cox’s Bazar, MSF International President Joanne Liu spoke at a conference organized by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. “It’s hard to comprehend the magnitude of the crisis until you see it with your own eyes,” she said. “The refugee settlements are incredibly precarious. They look like makeshift shelters made of mud and plastic sheeting, held together with bamboo and scattered across little hilltops… Let’s also not forget the root cause of the displacement of the Rohingya, which is the ongoing crisis in Myanmar. People do not flee their homes without good reason. They leave because their lives are in danger, and they have no other option. Hundreds of thousands of them still remain trapped in Myanmar, still living that terror and now cut off from humanitarian aid.”

MSF surveys conducted in the refugee camps in Bangladesh estimated that at least 9,000 Rohingya died in Rakhine state, in Myanmar, between 25 August and 24 September 2017. “We met and spoke with survivors of violence in Myanmar,” explained Sidney Wong, MSF medical director at the time. “What we uncovered was staggering, both in terms of the number of people who reported that a family member had died as a result of violence and the horrific ways in which they said they were killed or severely injured. The peak in deaths coincides with the launch of the Myanmar security forces’ latest ‘clearance operations’ in the last week of August.” The report’s conclusions were unassailable: the Rohingya were deliberate targets of abuses perpetrated in Myanmar.

Recalling his trip several weeks later, Saman remembered what he had witnessed. “In general, it is the most vulnerable people that I saw—elderly men and women, children, and unaccompanied young mothers with their children—that resonate in my mind,” he said. “But a recurrent thought is how most of us, even after witnessing first-hand similar crises in different parts of the world, have absolutely no point of reference in understanding what it is like to be a refugee.”

Ethiopian refugees prepare to board the buses that will transfer them from Al-Hashaba transit camp to Um Rakuba refugee camp. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosEven today, outbursts of violence force entire populations on every continent to flee their homeland—more than 80 million people have been displaced or have become refugees. Contrary to popular belief, 73 per cent of them have taken shelter in a neighbouring country. The Ethiopian refugees in Sudan illustrate this. In early November 2020, fighting broke out in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia between regional armed forces and the national army. Some 60,000 people sought refuge on the other side of the border, and hundreds of thousands were displaced inside Tigray. MSF got to work on the Sudanese side as soon as the first refugees arrived, providing support and medical assistance. In December, photographer Thomas Dworzak went to the Al-Gedaref region to meet the refugees. This influx is hardly new. Waves of Ethiopian refugees arrived there during the 1985 humanitarian crisis. Now, 30 years later, the former refugee camps in the area have become communities, and the Ethiopians living there have become integrated.

-> L'intégralité du photoreportage de Thomas Dworzak au Soudan

The sun sets in the village of Al Hashaba, an entry point for Ethiopian refugees. Sudan 2020

© Thomas Dworzak / Magnum PhotosLatest photo-reportages

Greece: Trapped in island camps by Enri Canaj, 2020

Sudan: Refugees at the border by Thomas Dworzak, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack by Newsha Tavakolian, 2021

Mossoul, When The Birds Will Fly Again by Nanna Heitmann, 2021