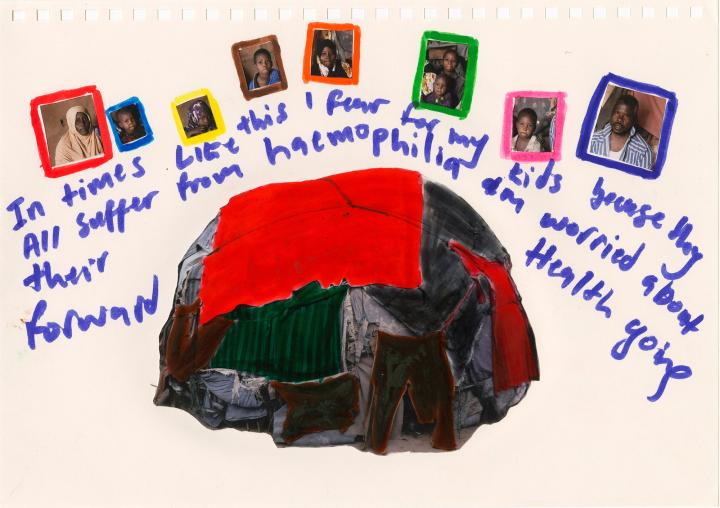

Conflict zones and violent realities

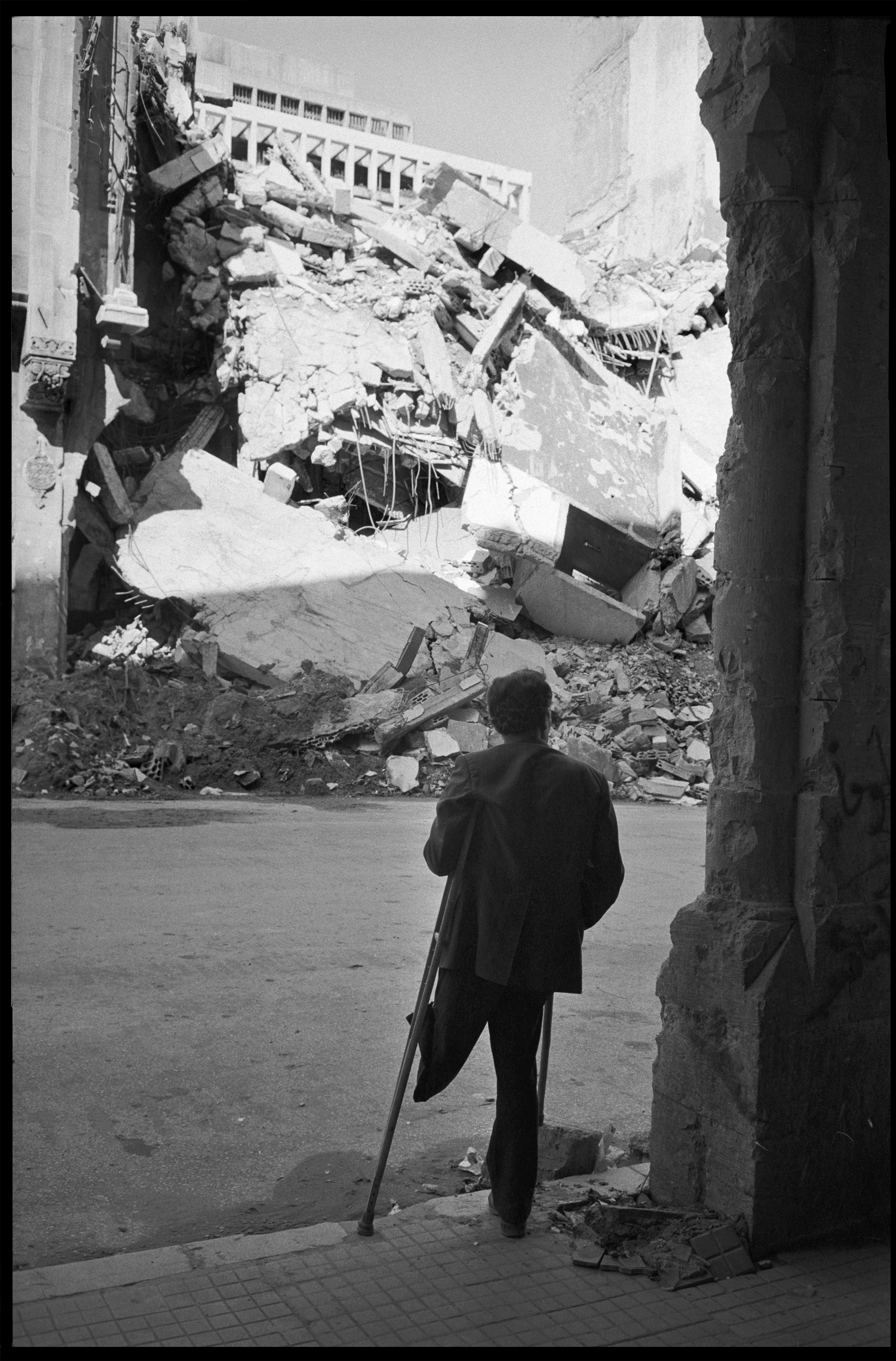

Lebanon, 1977. A man whose left leg was amputated, possibly as a result of the civil war, looks at a building destroyed by bombing in Beirut.

© A. Abbas / Magnum Photos“We were treating people under sniper fire.” That’s how an MSF staff member who had just returned from Lebanon described his experiences in the 14 June 1976 issue of the medical journal Tonus. The civil war, which began in the spring of 1975, was the first time that MSF had worked in the midst—rather than on the periphery—of a conflict. Over nearly a decade of violence, more than a dozen Magnum photographers covered the realities of life for Lebanese people trapped between shifting and sometimes abstract front lines. In this extreme context, as in so many contemporary conflicts, photographers assumed the role of witness, as did humanitarian workers who incorporated it into their aid mission. For 50 years, they have recounted, each in their own way, the complexity, distress, and dignity of people who survive senseless violence.

Facing risks at the height of combat

In late 1975, at the request of the Palestinian Red Cross, MSF began working in Beirut’s besieged Nabaa-Borj Hammoud district. This isolated Shiite enclave, located in a predominantly Christian area, was home to 100,000 people who were cut off from the rest of the world. The small MSF team, composed of a surgeon, anaesthetist and two nurses, worked around the clock to treat the wounded people streaming in. The humanitarian workers lived in the same conditions as the residents of Beirut. Lacking electricity, radio, or any other means of communication, team members took turns working in the capital until July 1976, when the hospital had to close at the height of the fighting.

By their actions, the humanitarian workers chose to experience the internal violence alongside Beirutis so that they could be as close as possible to the reality of the needs. Standing with civilians means remaining close to the most vulnerable people, who are also the least visible. The humanitarian worker’s role is truly meaningful only when that goal is achieved.

Children play in damaged cars near Sabra and Shatila camps in Beirut. Lebanon,1983

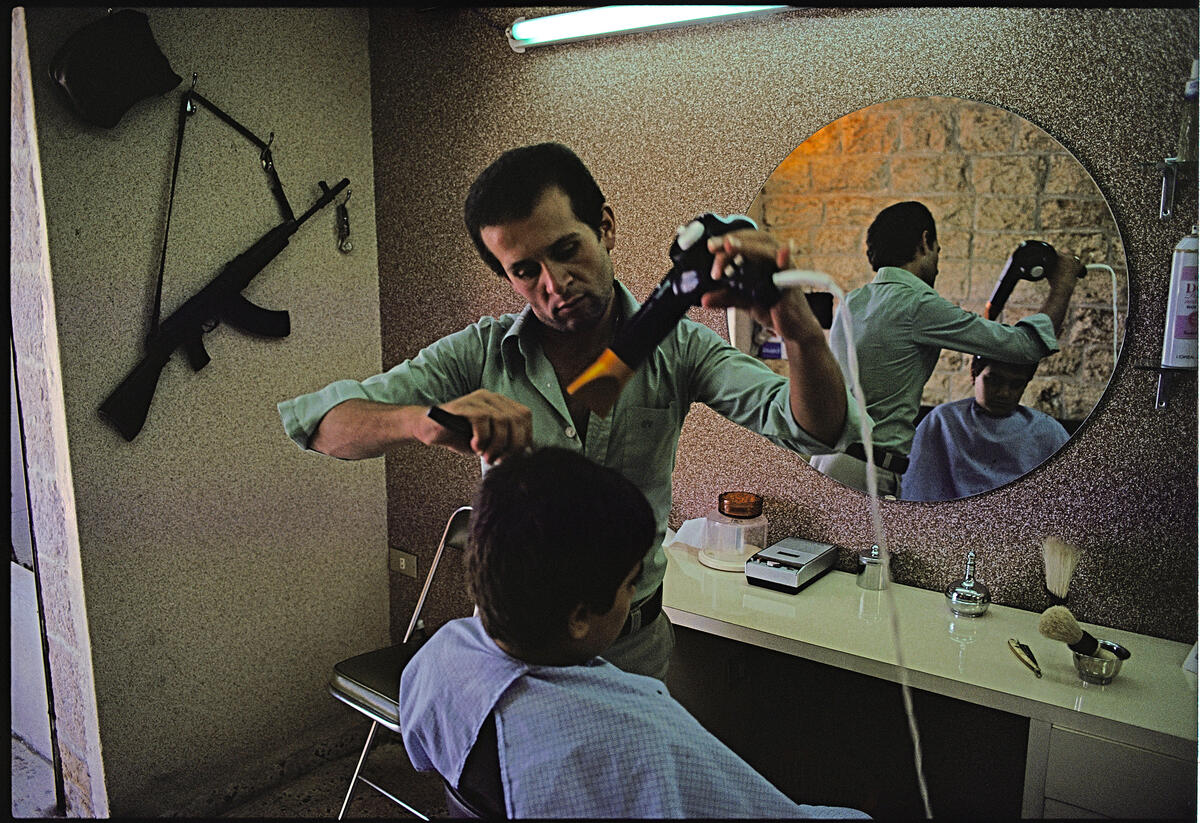

© Chris Steele-Perkins / Magnum PhotosSimilarly, for photojournalists, documenting war involves more than simply observing military tactics and explosions. Most importantly, it means seeing what civilians see and being with them. That was what Raymond Depardon chose to do. During the month he spent in Beirut in the summer of 1978, he tried to document every aspect of this reality and, above all, both the consequences and the secondary impacts of the conflict.

“The Muslims, the Christians, the city, the beaches—Beirut was a land of contrasts at that time,” Depardon wrote. “But freedom of movement and action are relative in the midst of a civil war. I learned to understand, to walk, to circulate, to hide my passes in my shoes, to not make a mistake. I definitely did not want to mix up the pass for the Christian side with the pass for the Muslim side.”

MSF workers told the same story. “Our vehicle did not bear any distinctive marks,” an MSF nurse reported in the organisation’s internal journal in 1986. “While such identification might have been useful on one side, it would’ve created a major risk for us on another. We relied on Muslim and Christian drivers who took turns so that we could travel through the different areas of Beirut and get to our hospital in the combat zone.”

Because every war involves political stakes, the parties to the conflict seek to gain advantage any way they can. Like photographers, humanitarian aid workers must negotiate constantly to ensure that their work space is secure. Thus, in 1978, thanks to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), a three-hour ceasefire was arranged so that a vehicle carrying MSF staff could enter the besieged Christian town of Zahlé. They remained until the city was bombed in 1981. A similar situation occurred in Deir el-Qamar in 1983. The next year, MSF withdrew because the safety of its staff could no longer be guaranteed.

While it is critical to have a physical presence close to the clashes, danger is always present. There are many constraints, requiring both humanitarian workers and photographers to adapt to and evolve in an ever-changing environment.

Obtaining access and safeguarding the humanitarian mission

“There may still be a specific moment when you cross the line between precaution and risk,” said Dr. Alain Dubos, describing MSF’s assignment in Chad in 1980. “The war is there, close by. It may break out in unpredictable ways. The logic of war is a mystery whose secrets are known to only a few initiates. For a team that is propelled, within a few hours, to the edge of the inferno—or even into its very heart—the immediate need is to adapt. This can happen in the midst of a sudden explosion of weapons fire.”

Starting in 1979, armed groups fought for control over N'Djamena, the capital city of Chad. People fled to neighbouring Cameroon, where an MSF team was working. In April 1980, MSF doctors were also in Chad’s capital, treating wounded people in two hospitals. Given the level of violence, the priority need was for emergency care—specifically emergency surgery. To maintain their neutrality, the humanitarian workers provided aid to people on both sides of the conflict throughout the country. However, rumours flew, claiming that the medics were helping smuggle weapons to the rebels. Libya’s support for one of the parties to the conflict led to a burst of violence and increasing insecurity. In January 1984, two MSF staff members were kidnapped and held hostage for two months.

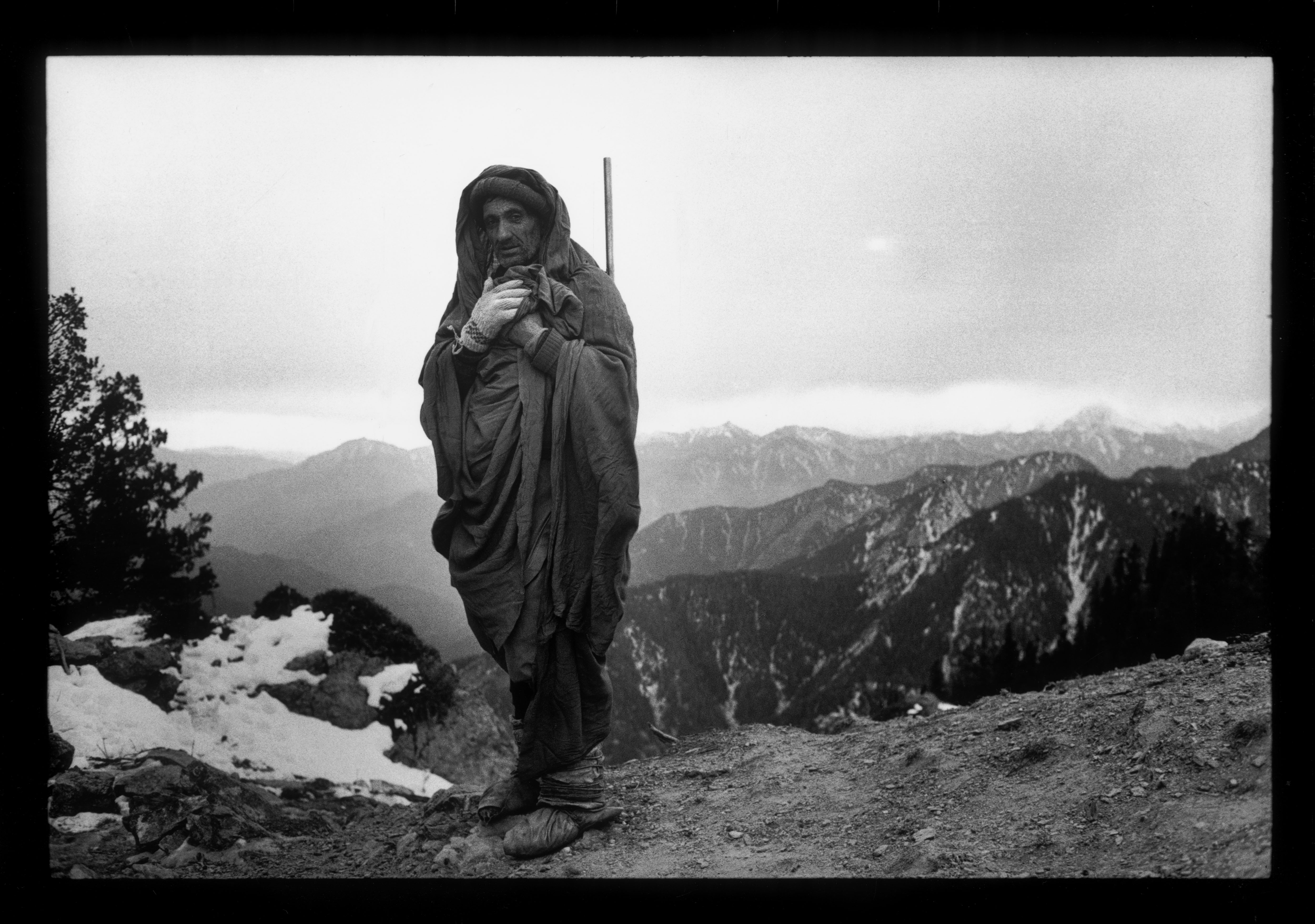

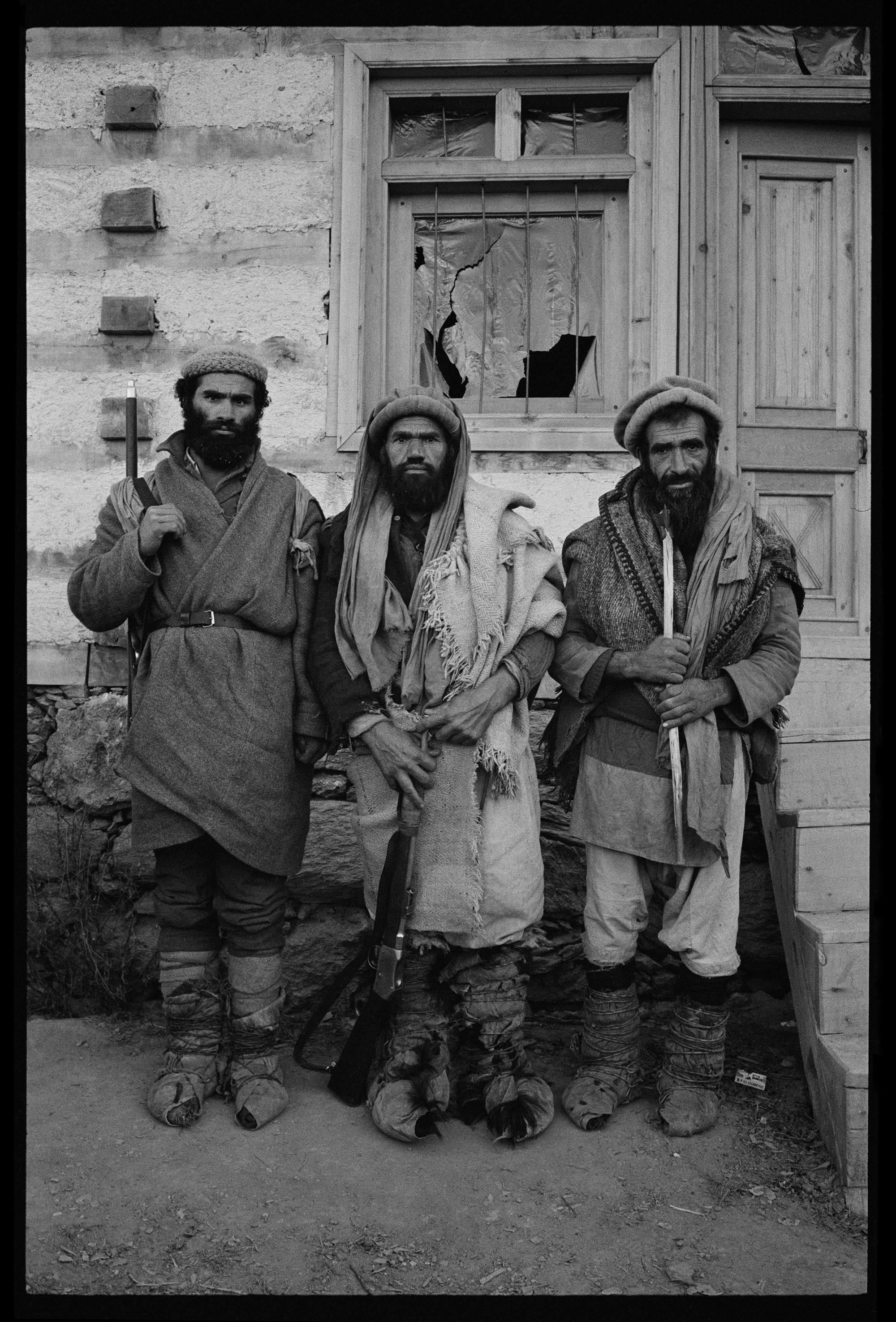

In Afghanistan in the late 1970s, photographers and humanitarian aid workers were some of the only outside witnesses to the violence ravaging the country. In 1978, photographer Raymond Depardon began to document living conditions in Nuristan, a province bordering Pakistan, where people rose up against the new Soviet-backed government in Kabul. Claude Malhuret, then president of MSF, sent an exploratory mission to the region after Depardon’s reporting appeared in Paris Match in April 1979.

Juliette Fournot, MSF head of mission in Afghanistan from 1982 to 1989, grew up in the country. “I know this country well,” she said. “I speak their language. They think of me as a sister. I believe that I have a moral duty to do what I can to provide them this medical aid, which is really much more than just that. They have been abandoned altogether throughout this interminable war.”

Armed men observe the area from a hill in Logar province. Afghanistan 1984

© Steve McCurry / Magnum PhotosIn 1980, MSF set up a clandestine mission in the northern part of the country. Four tons of medical supplies were delivered by mule and horse across the Afghan mountains. The trip took 35 days. MSF’s small hospitals primarily treated women and children, the main victims of the conflict. “I’ve seen the war and its consequences,” said Fournot. “Children mutilated by mines, their legs infected, necrosis setting in for lack of treatment. I said to myself, ‘You’re staying.’” Families streamed in from every valley. MSF treated nearly 3,000 people each month.

The doctors were the only people who knew the reality of life for Afghans in these remote provinces. MSF decided to speak out and alert the public. In an op-ed published in Le Monde on 25 September 1984, Malhuret wrote that every person had a responsibility to end the slaughter. “By denouncing what was taking place there, we were ‘treating’ many more people than by providing aid to the few Afghans we were able to reach.”

Despite efforts to mobilise the international community, MSF’s facilities were bombed regularly by the Soviet army in the 1980s. The situation worsened over the years, and the lack of security eventually forced MSF to suspend its work in 1990. Humanitarian neutrality was no longer enough: rivalries among armed factions of the mujahideen led to attacks, thefts, and hostage taking. In April 1990, Frédéric Galland, an MSF logistician working in the Yaftal hospital, was killed. The humanitarian workers decided to leave the country.

People walk past bombed-out buildings in Kabul. Afghanistan 1995

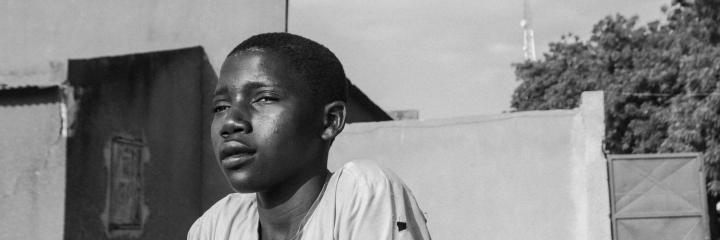

© Steve McCurry / Magnum PhotosDarfur 2003: another context, another time, but the same outburst of violence and the same challenges to achieving the humanitarian objective. This conflict, between rebel groups and the Janjaweed militia armed by the Sudanese national government, led to more than 300,000 deaths and displaced thousands of people. Elsafi Mahadi Bushara is from Darfur and serves as MSF’s logistics manager in Sudan. He remembers life before violence exploded in his region. “Before the conflict, the tribes lived in peace,” he said. “No one travelled with a weapon. There were no dangerous places. You could travel without a cent in your pocket. People would welcome you everywhere and share a meal. In 2003, the political division between Arab and non-Arab destroyed Darfur. ‘Take what you want’ became the watchword. ‘Take the land and the property, and kill those who remain.’”

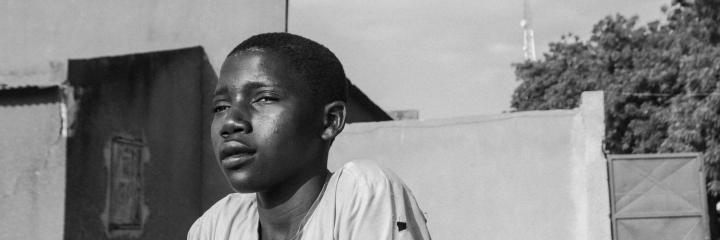

Photographer Paolo Pellegrin went to southern Darfur to capture the impact of recurring waves of violence on displaced people. Their living conditions were extremely precarious, with children among the worst affected.

A girl living in a displaced persons’ camp in Zelingei, South Darfur, looks into the camera. Sudan 2004

© Paolo Pellegrin / Magnum Photos

Humanitarian organisations were present in Darfur, but the authorities restricted them to working only in the displacement camps before expelling most of them. Nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) were accused of supporting the enemy. “Because the NGOs were working in the rebel zones, I was arrested and accused of dealing in stolen goods for MSF,” Bushara said. “The authorities couldn’t find any evidence, and I was released. Later, MSF was expelled from the country. In two hours, we burned all the archives so that the authorities couldn’t harass the local staff or the patients. To do that, I rented a bakery with a huge wood-fired stove.”

The silent diplomacy strategy—which involved bilateral discussions warning the international community, including the United Nations, about the violence and obstacles to aid delivery— was unsuccessful. Today, the scars are still visible in Darfur. Outbreaks of violence continue and millions of displaced people remain in camps, prevented from returning home.

Humanitarian workers and photographers may lack the means to stop a war, they work relentlessly to ensure that people in power are faced with the consequences of their actions and inactions.

Taking action and prompting others to respond

Treating wounded people may not be enough. “For once, MSF workers have broken the silence that surrounds their work.” Those words appeared in the 14 June 1976 issue of Tonus. “One of the staff members observed the human folly unleashed in Lebanon, tearing it apart, and decided to speak out.” That was the first time that the young organization grasped the importance of telling those stories and providing information beyond the rhetoric of the warring parties. In addition to statements from MSF staff, photographers also had a role to play. Without photographs, one might think there were no victims. But photography connects the viewer with the individuals affected, erasing the distance that separates the war zone from the observer. Photography mediates the gaze between victim and observer. This intermediary is the photographer, who frames and grasps the reality that he or she understands.

A family gathers on their balcony to look out over the city of Aleppo, the scene of intense fighting during this period of the conflict. Syria 2012

© Emin Özmen / Magnum Photos"I lost faith in many things, but I continue to believe that documenting history is essential for history and collective memory,” said Magnum photographer Emin Özmen, who is from Turkey. “We must not forget what happened. In 2012, one year after the [Syrian] conflict began, fighting had reached the border with Turkey. In June of that year, Aleppo, which is 60 kilometres [37 miles] from that border, was targeted by intense aerial bombing. This tragedy was taking place at my country’s doorstep, just one hour away. I was really upset and worried. I thought about it all the time. Given the nature of my work—photography—and knowing that a war had broken out so close to me, I couldn’t just stand by. So I decided to cross the border to document and bear witness to what was happening."

However, the Syrian reality is not easy to grasp. Cross-checking and confirming statements and accounts is essential. Taking the time to do that is critical because it’s impossible to obtain transparent and clear information in an ever-changing environment.

Opponents of the Syrian regime demonstrate at an early morning rally in the centre of Hama. Syria 2011

© Moises Saman / Magnum Photos"When the Arab Spring revolutions began, things were moving too quickly and you had to cover the news,” said photographer Moises Saman, who was in Syria in 2011. “I didn’t have time to step back and question myself. However, over time, I realized that in visual terms, just covering the events would not help the public understand the complexity and implications of this historic transformation. Over the course of my five years in the region, I saw with my own eyes how easily the roles of victim and perpetrator can change. It became impossible for me not to challenge simple accounts of good versus evil. It was in this very landscape, this changing landscape, that I found my focus and was able to question my own role and confront my doubts."

Free Syrian Army fighters move on the front line of Al-Arkub, in Aleppo province. Syria 2012

© Jerome Sessini / Magnum PhotosPhotographer Jérôme Sessini was also in Syria—in Aleppo—in 2012, in the midst of the post-Arab Spring clashes. “I had my own opinion about the situation in Syria, some ideas, some preconceived notions,” Sessini said. “But the first thing that struck me most powerfully was the number of civilians who’d been killed. You often hear, ‘This many fighters were killed, this many soldiers, this many troops.’ But what I saw in Aleppo was that many, many civilians were killed.”

A woman is surrounded by members of her family as she sits beside the body of her son who was tortured and killed by pro-Assad militias in the city of Aleppo. The young man’s body was found in the street and brought back to his village for burial. Syria 2012

© Moises Saman / Magnum PhotosStarting in 2011, in addition to its direct work with Syrians, particularly in camps for displaced people, MSF provided clandestine support to many health facilities in the country, working through unofficial networks.

In 2015, a surgeon receiving MSF support in the rural northern part of Homs governorate spoke of his constant fear of aerial attacks, and yet determination to stay on to perform surgery. “I am the only general surgeon for a population of 100,000 people,” he said. “Most of the surgeons have fled. This is a difficult situation on both the personal and emotional level. I can’t leave and abandon all these people—no other surgeon would obtain authorisation to enter this region. But I’m not happy here. My wife and children are in constant danger. On the one hand, I’m not satisfied with this situation; and on the other, I know that an entire population needs us desperately.”

In 2013 and 2015, MSF denounced the use of chemical weapons after treating a large number of patients whose symptoms were consistent with exposure to them. Today, 10 years after the Syrian conflict began, MSF continues to work in the country and in refugee camps for Syrians in neighbouring Lebanon and Jordan.

A woman who had recently returned to the city of Kobané feeds her twin sons. Syria 2015

© Lorenzo Meloni / Magnum PhotosModern conflicts are characterised by their complexity. Against that backdrop, humanitarian workers and photojournalists seek, above all, to convey diverse perspectives and voices. They bring facts and events to life. Beyond damage assessments and casualty counts, images and stories document the violence of destruction and loss. That way, no one can say, after the fact, that they didn’t see or didn’t know.

During the battle to retake the Iraqi city of Mosul from the Islamic State, four Magnum photographers were there in 2016 and 2017: Paolo Pellegrin, Jérôme Sessini, Lorenzo Meloni, and Moises Saman.

In late October, Peshmerga forces stormed Omar Qapchi, a village east of Mosul. After an armoured convoy encircled a force of approximately 12 Islamic State fighters, Kurdish soldiers chased their enemy on foot through the streets. Iraq 2016.

© Paolo Pellegrin / Magnum Photos

Iraqi forces treat an injured child and other wounded civilians in Mosul after Islamic State fighters launched a mortar and car bomb attack there. Iraq 2016

© Jérôme Sessini / Magnum Photos

Civilians flee Mosul. Iraq 2017

© Lorenzo Meloni / Magnum Photos

Displaced Iraqi civilians from the west side of Mosul gather at in informal camp on the periphery of Hammam al-Ali, south of the city. Iraq 2017

© Moises Saman / Magnum PhotosThe offensive by Iraqi troops and US-led coalition forces lasted for nine months. Every street and every house were visited and secured. Over time, the front line shifted. With thousands of Iraqis wounded or killed, and more than one million displaced, this urban battle remains one of the deadliest since World War II. While seeking a secure workspace in the city centre, in February 2017, MSF set up a mobile war surgery unit to treat evacuated people outside of Mosul. For several months, it was the facility closest to the fighting underway in western Mosul. More than half of the war-wounded people in this area of the city were treated there. In June 2017, MSF began working in the Nablus district, a strategic point located approximately three kilometres [1.8 miles] from the front line. The teams treated people injured in the conflict in the emergency department and in the operating room. At that point, the Nablus hospital came to reflect the horrors the battle of Mosul was inflicting on residents. The teams performed several hundred operations over the course of a few weeks.

Trish Newport, project coordinator in Mosul in 2017, describes getting to know one of MSF’s security guards and what he shared with her. “The first time I met Mahmoud, he was walking along the West Mosul Road,” she said. “The war was raging less than two kilometres [1.2 miles] away. He was carrying a mint plant as he walked. My team and I were looking for a large room where we could set up a stabilisation unit for the wounded. We wanted to be close to the front line to increase patients’ chances of survival during their ambulance transfer to the hospital. Large rooms were hard to find because most of the large buildings had been destroyed during the war. We stopped Mahmoud along the road and asked him if he knew where we could find such a room. He showed us several buildings. Each time we visited a building, he always had his pot with the mint plant. Once we had chosen the location for our clinic, we hired him as a security guard. He came to work every day with his mint. Mahmoud and his family had lived in Mosul for the last two-and-a-half years, under the Islamic State. During the occupation, he had taught his children how to garden and his youngest daughter had planted mint. When he sent his children to the camp for displaced people, she asked him to take care of her plant. He promised to keep it with him until she returned. And that’s what he did. That plant sheltered all of us. On days when the bombing or the fighting was particularly intense, I would look outside the clinic and see Mahmoud sitting calmly in his guardhouse with the plant in his lap. When my assignment was over, Mahmoud brought me some mint seeds and asked me to plant them where I live, in Canada, so that the plants could have a better life.”

As humanitarian workers and photographers try to understand the complex realities in a conflict zone, they must survive the same extreme conditions as the civilians. Whatever the context, they want to be there, with the local communities, to bear witness and speak out. Most often, we remember the wounded and the dead. But it is more essential to pay attention to the people who survive in these extreme situations. This is the miracle of survival. The work of these humanitarians and photographers helps to ensure that the survivors are not forgotten that they remain with us—whether in photo archives or written accounts. That is the importance of this work: bearing witness to these lives and fighting against forgetfulness, or indifference.

Latest photo-reportages

Greece: Trapped in island camps by Enri Canaj, 2020

Sudan: Refugees at the border by Thomas Dworzak, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack by Newsha Tavakolian, 2021

Mossoul, When The Birds Will Fly Again by Nanna Heitmann, 2021