Meaningful days with refugees

The first camp in Dadaab, Kenya, was set up thirty years ago to host Somalis fleeing civil war. At its peak, the Dadaab Refugee Complex hosted some half a million people. Many refugees living in the camps today have been there for three decades; others were born in the camps and have known nothing else. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has provided healthcare to refugees in Dadaab for most of the camp’s existence. They first set up activities in the camp in 1992 and are now the main healthcare provider in Dagahaley camp. During a recent visit to Dadaab, South African photographer Lindokhule Sobekwa met generations of families born and raised in the camps, prompting him to question his own idea of what it means to be a refugee.

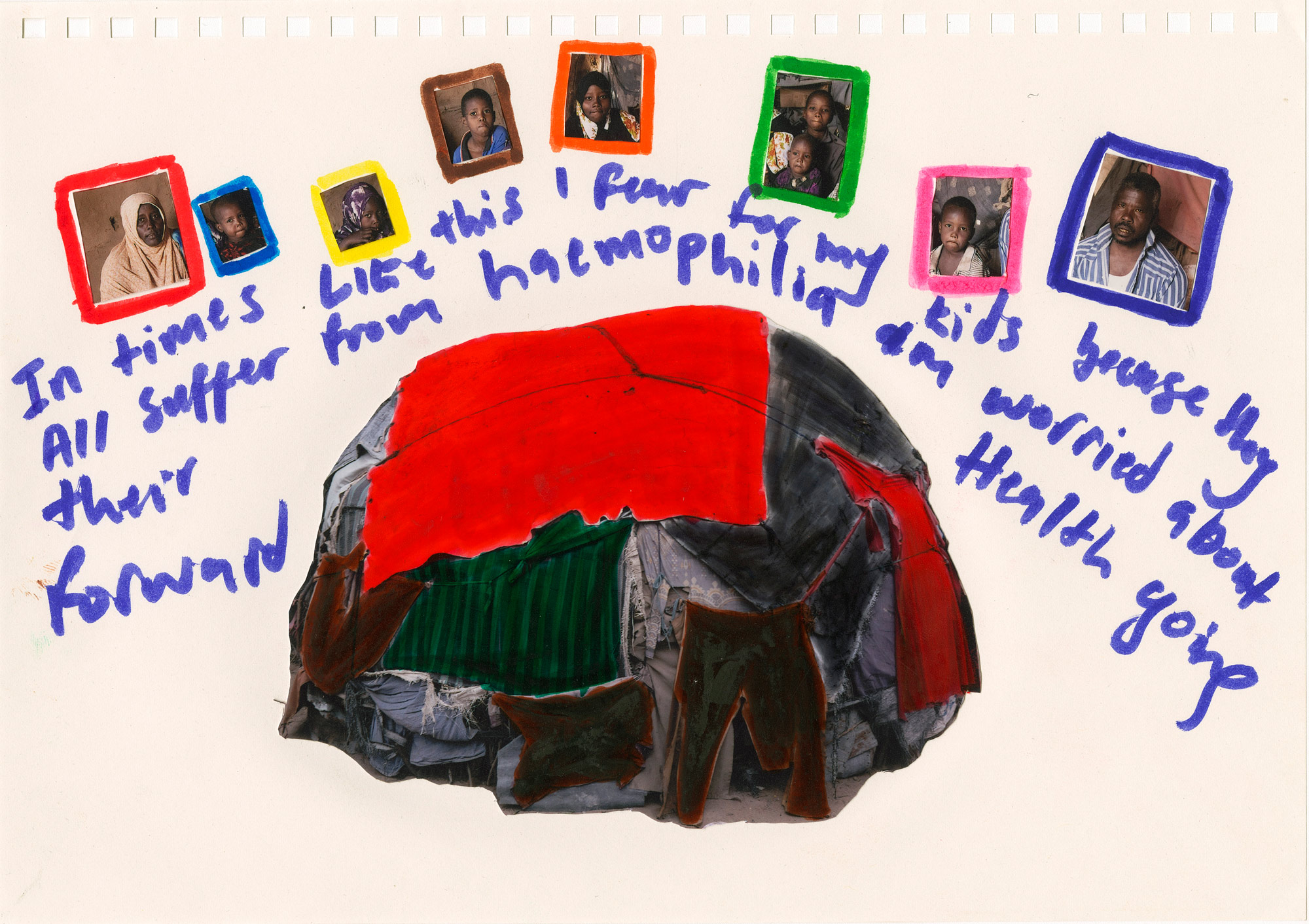

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley. 22 June 2021. Family group portraits. Fathima and her husband were some of the first people to flee Somalia in 1991. They were married in Dagahaley camp and gave birth to 12 children. Four of the boys suffer from haemophilia and Fathima worries about their health since the threats of shutting down the camp.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum PhotosDiscovering the rough reality of the camp

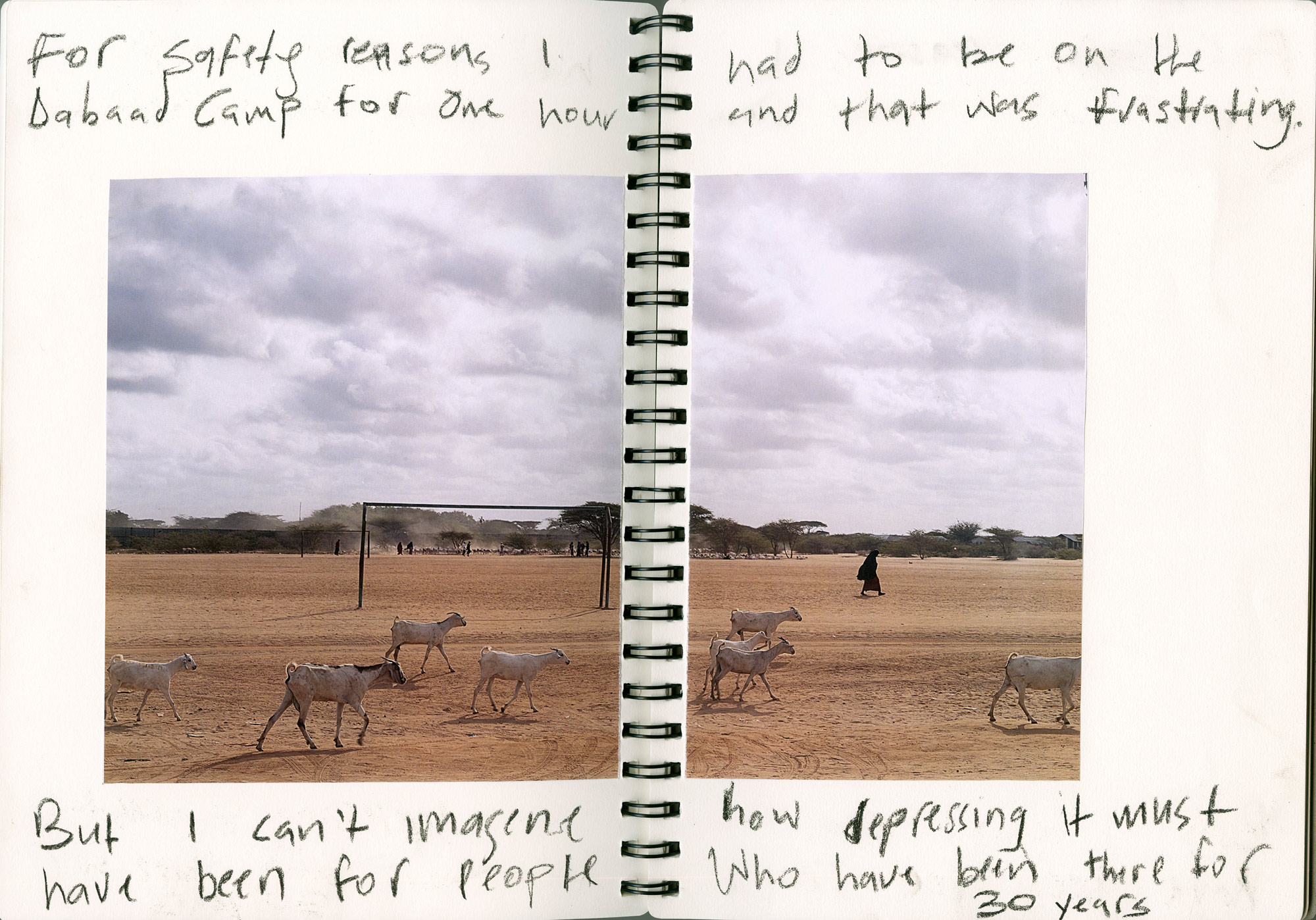

It sounds strange to me to call someone a refugee. I’ve always heard people talking about refugees, but I didn’t know that the biggest camp in the word is actually Dadaab, Kenya. I wanted to see for myself what the place looks like and what kind of challenges the people there face. Of course, I can't tell you what their challenges are. The people living there know the realities much better than I do. But I can tell you about my own intense experience of the place.

I'd been to Kenya before on a different assignment, but I didn't know anything about Dadaab and it was the first time I’d been to a refugee camp. I knew of the Somalian tensions, because it’s reported in the South African news, and also because there are Somali people living in my country and some of them are my friends, but they never mentioned the refugee camps. There have been numerous xenophobic attacks and killings involving the Somali people who live in South Africa. But no matter what happens to them here, they still choose to stay. Similarly, when I went to Dadaab, most of the families I interviewed said they would never go back home. Home is not an option for them. They would rather go to a different country or stay in the camp, even if it’s a dangerous place.

When the plane was landing I saw out of the window what Dadaab looks like. I remember I had a feeling I’d never felt before: nervousness mingled with excitement. Maybe the same feelings as when they arrived there. The nervousness was rooted in what I’d read before my trip. And the excitement was because of how beautiful the landscape looked and how photogenic it is. The people I met in the camp were really friendly; for example, when I was working in the market, shooting, everyone was smiling and I just felt at ease. But, alongside this warm welcome, I also tried to bear in mind what I’d read in the news - stories of people being abducted - which is also a reality.

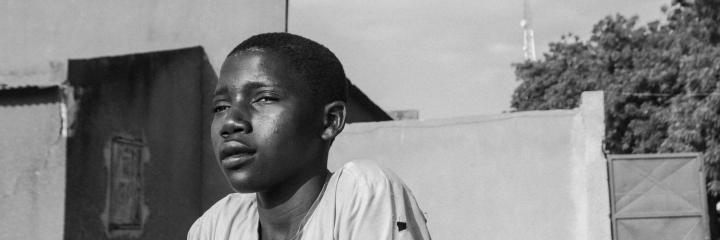

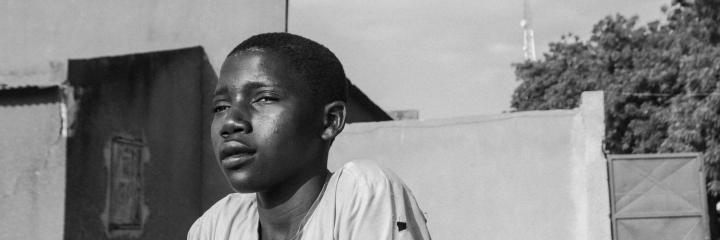

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley Camp. 20 June 2021.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum PhotosCollaging the collective experiences of refugees

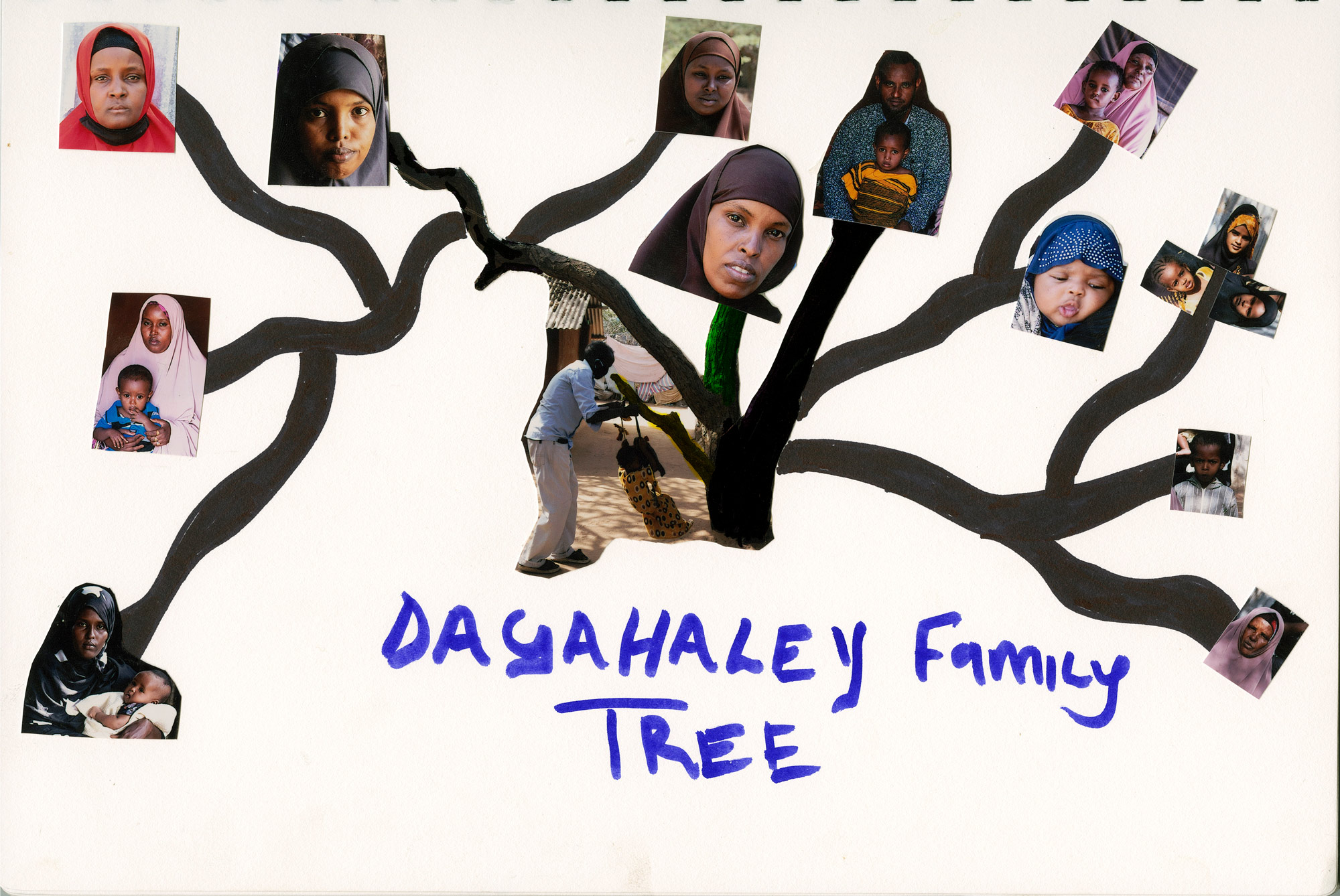

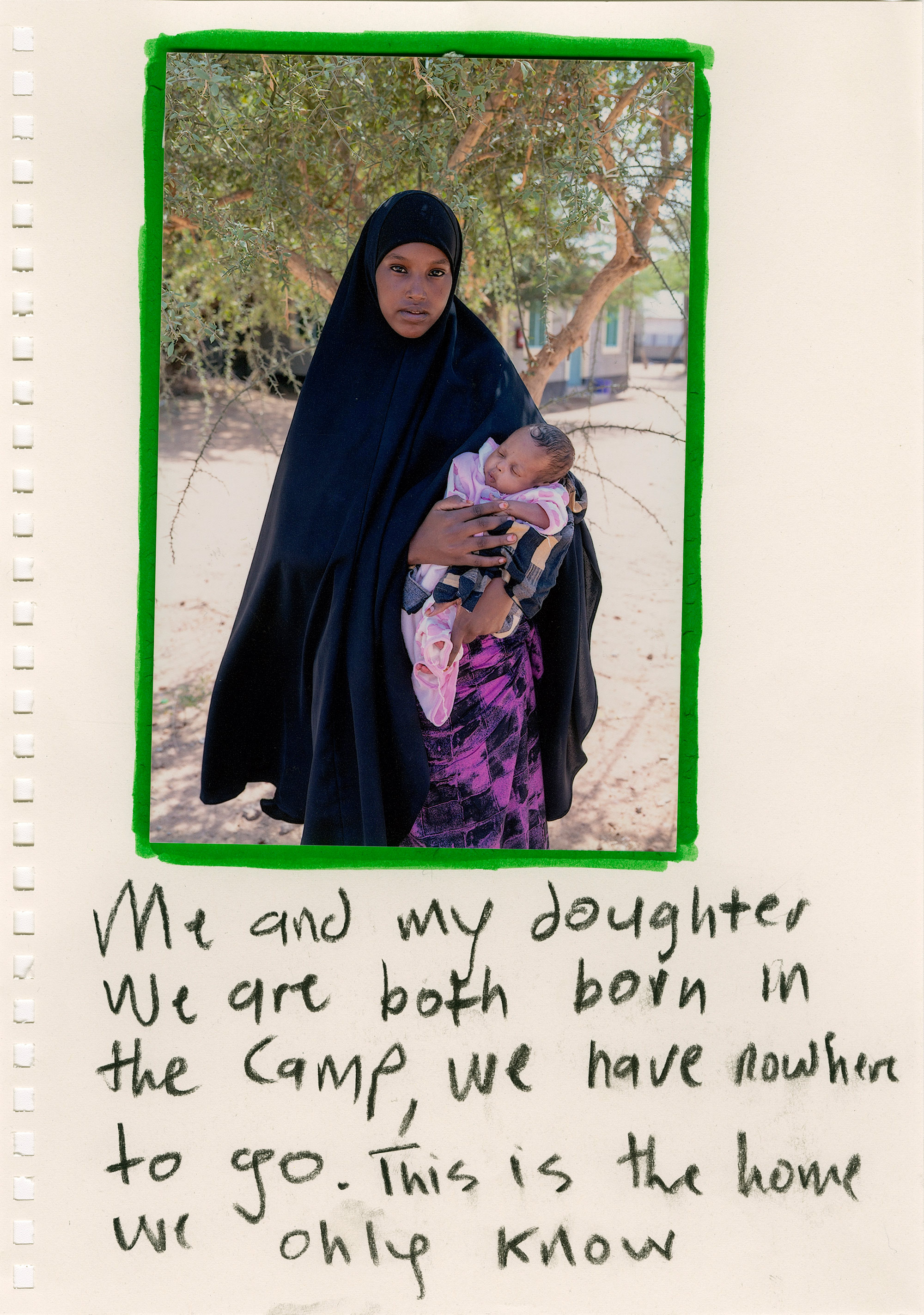

I found many unique stories in Dadaab. Before taking portraits, Paul, the MSF Communications Officer, and I interviewed everyone I was photographing to understand who each of them was, where they were from and how long they had been in the camp. Some mothers who brought their newborn children to the hospital to be vaccinated told me they themselves were born in the camp and know nothing about Somalia. They can only imagine what Somalia is like through the stories they were told by their parents. Now, a second generation of children has been born in the camp. Most of them have parents who left Somalia in the early 90s during the peak of the tensions. It was interesting and sad to hear that they had also been born in the camp. They all worried about the news of the closure of the camp, but it isn’t the first time the authorities have made this kind of announcement.

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley. 29 June 2021. A collage representing the family tree of a refugee family.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum Photos

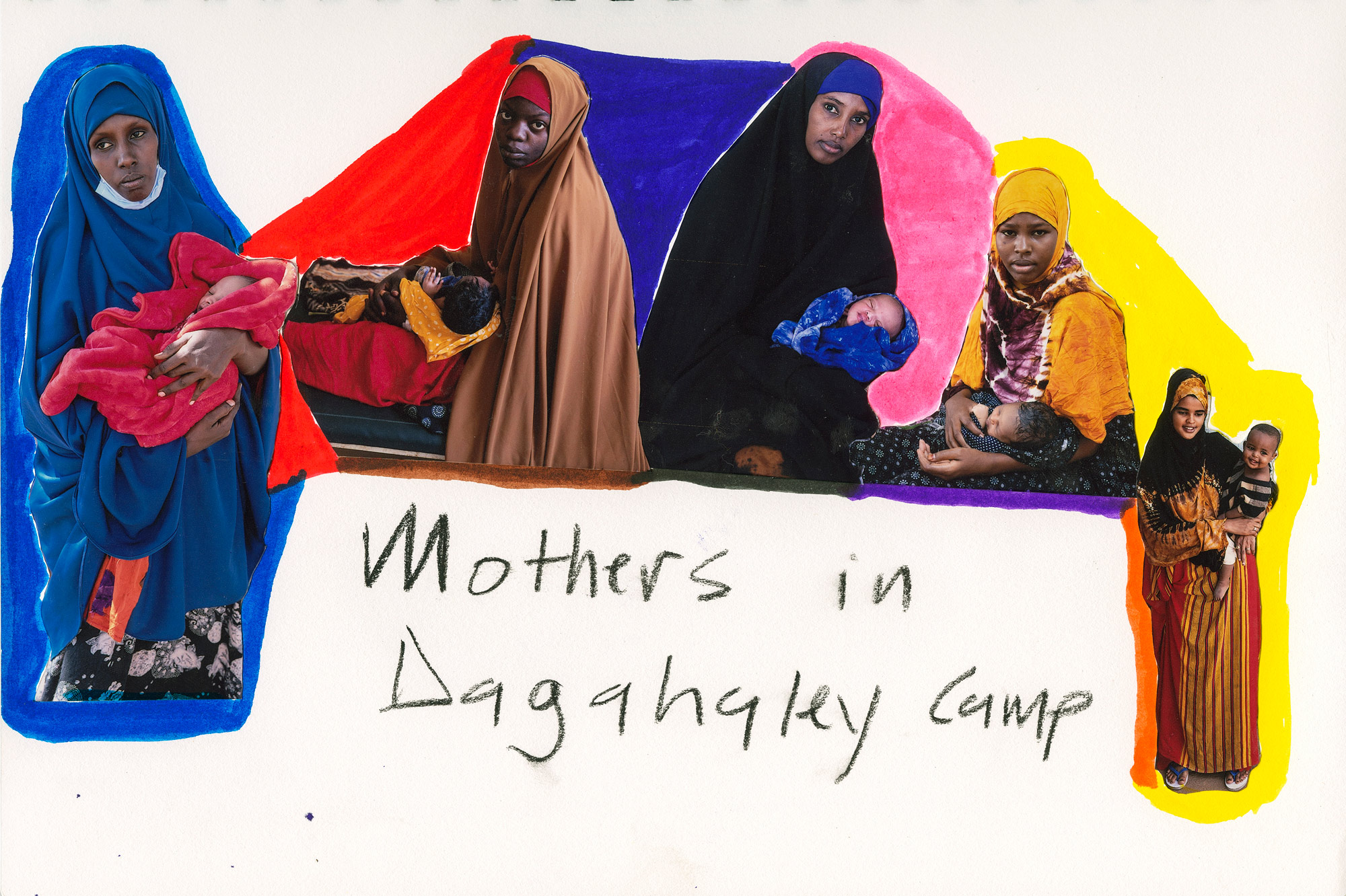

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley, 13 June 2021. Collage portraits of mothers who came to the MSF hospital to immunise their children or give birth. All these mothers were born in the camp and have never been to their homeland of Somalia.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum Photos

Kenya.Dadaab, Dagahaley Camp. 23June 2021.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum Photos

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley. 13 June 2021. Portrait of a new mother who has come to the MSF hospital to immunise her firstborn child.

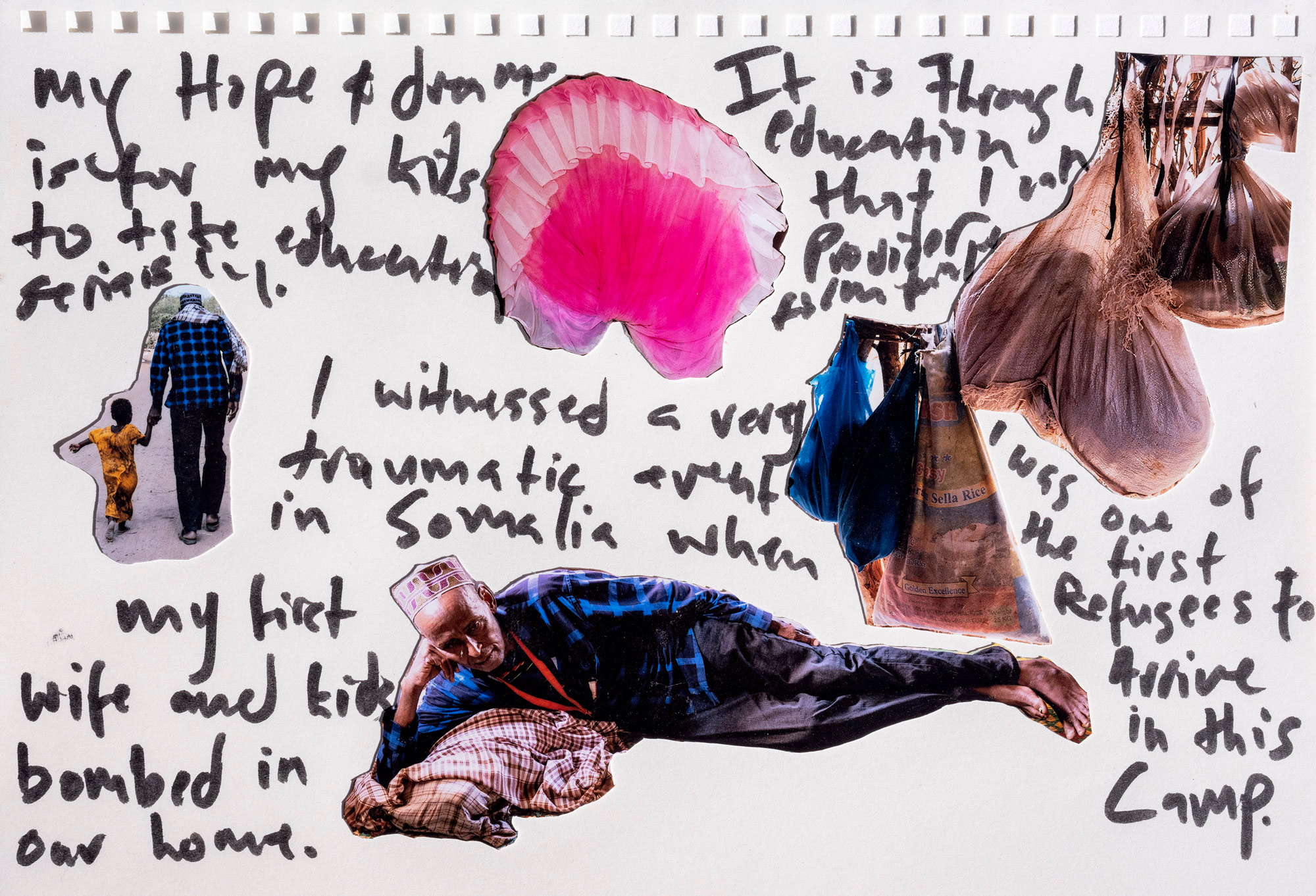

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum PhotosThrough the conversations I had with the refugees about the camp, I had the idea of using collage to tell their stories. Because there were so many stories that often interconnected, collaging individual experiences into a whole made sense for me. For example, I created a collage of a father lying on a blanket. Within the same image there’s another image of him walking with his daughter, and also a few of his clothes and other personal items. His name is Khasim and he left Somalia in the 1990s. He experienced a traumatic event that still haunts him today. He witnessed his first wife and their children being bombed. I think he was coming home from work and was about to enter their house when there was an explosion. His whole family died like that. He came to Kenya on foot with his siblings and MSF was one of the organisations that helped him at that time. He was later recruited by MSF along with some other refugees and was one of the first people to work for the organisation to run health promotion campaigns. Khasim is in his fifties now; one of his children is my age and is currently studying medicine. His family is trying to find a way for him to continue his studies in Kenya, or maybe abroad. Education is the only hope for Somali refugees in Kenya to escape their dire situation.

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley. 17 June 2021. Khasim left Somalia in 1991 after he witnessed a traumatic bombing that killed his first wife and children. When he arrived at the camp he remarried and started a new life. He was one of the first MSF staff members in the early 90s and was able to study. He now works as an immuniser. His hope is for his children to pursue education as a way out of the camps.

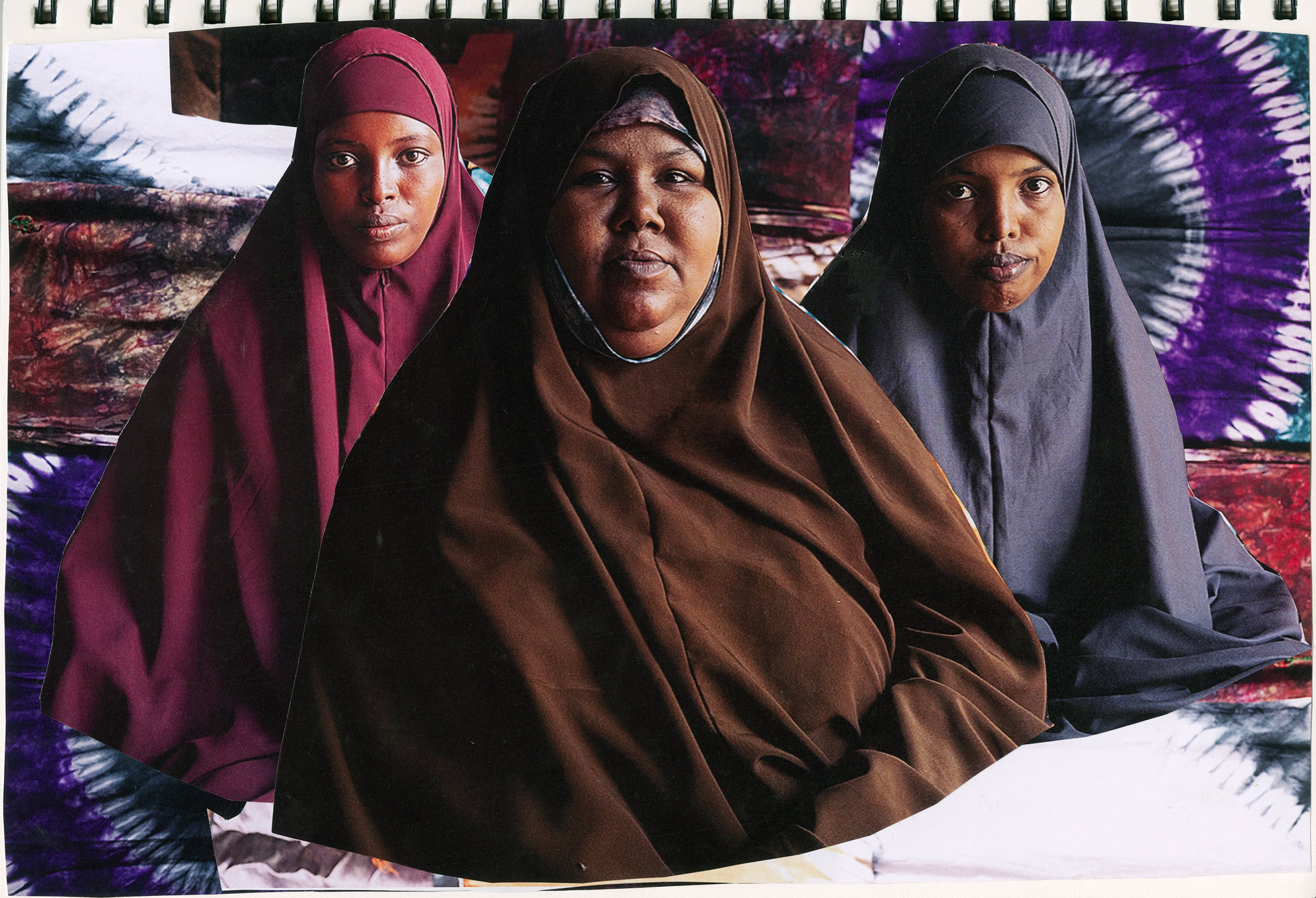

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum PhotosIn another collage we see three women, one in the foreground and two in the background. Their story is interesting. One of them came to the camp in 2007. She belonged to a minority tribal group in Somalia and her husband belonged to a majority clan. She decided to flee Somalia because of the abuses she faced from her husband and his family as well as for security reasons. When she arrived in Dadaab she was having psychological trouble so she joined a group that works to empower women. This programme helped her develop skills and tools to overcome her difficulties.

These groups help women to be independent and empowered. She mentioned that some members of the community were against this idea of giving women a voice. As a result she was shot, but no one knew who shot her. She showed me the bullet wound. Despite all those obstacles she kept pushing and looking for new ways. Now she's an activist who is working to reduce the barriers faced by women in the camps. She also advocates for and promotes school attendance for girls. I thought this was a beautiful story.

I used the collage technique to bring these stories together. I was trying to reflect a collective experience of some sort, because the people I spoke with were all interlinked in a way. All the things they have been through together are a set of interconnected, collective experiences.

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley. 15 June 2021. Ifrah was born in Somalia in 1989. She fled Somalia in 2007 after being mistreated by her husband’s family, escaping to Dadaab Camp for safety reasons. Through participating in NGOs she learnt tie dye techniques, which she now shares with other women, helping them to be independent and collaborate with other NGOs that work to empower women in the camp.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum PhotosFocusing on the human

Witnessing the reality of the situation for refugees at Dadaab made me feel strongly that something should change to make space for a better life for these people. For instance, removing some restrictions in the camp and not limiting people’s living space or how many people can be there.

I did an interview with a lady who was born in the camp and I remember her saying that Somalia is not her home; it was her mother's home. She’s a refugee and she doesn't have Kenyan nationality, but that’s her dream. Because it would mean she belongs somewhere.

It’s also about normality. Refugee status creates a social group that is treated as lesser people. It’s not humane to have people living like this, locked up in a camp. And as a refugee, even if you are educated you don’t have the same opportunities and won’t be paid as much as a Kenyan citizen. The Dadaab camp has existed for 30 years. It needs to be a formal community. It has its own market and most other things that a community has. It’s not a camp where people live in houses made of plastic sheeting; their houses have proper structures: walls and a roof. All they need is a helping hand, to find their strength and have hope. The people I met in Dadaab really inspired me to keep an open mind and to think about the attitude held by many of the refugees: no matter what, just keep on pushing and one day something will come.

I think this experience made me realise how lucky I am to be living where I live. I'm really privileged to be able to have a passport to say I exist, to be able to go home. I know that there is someone in Dadaab right now who wishes they had the life that I live. I’m also privileged to be a photographer, to be able to translate one person's story for the rest of the world. I've always seen my role as a photographer as that of a critical observer, to be a mediator, a kind of link between people. I’ve always wanted my images to change something, even if it's just one person’s perception about a place, to bring their focus onto our shared humanity.

Kenya. Dadaab, Dagahaley Camp. 15 June 2021.

© Lindokhule Sobekwa / Magnum PhotosLatest photo-reportages

Greece: Trapped in island camps by Enri Canaj, 2020

Sudan: Refugees at the border by Thomas Dworzak, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack by Newsha Tavakolian, 2021