Ituri, a Glimmer through the Crack

Manyotsi, 32, holds her six-month-old baby who was conceived from rape. She says that she loves her baby nonetheless, because the child is innocent.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosStory by Newsha Tavakolian, co-authored by Sara Kazemimanesh

In the northeastern province of Ituri in Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), more than one million people have been displaced as a result of violence that has plagued the region since 2017. Looting, fires, and abuses have forced families to leave their homes and seek refuge in camps that don’t provide much more security. Displaced people also face the threat of epidemics, various infections due to lack of hygiene services, and sexual violence. They depend on humanitarian assistance to survive, but there are very few organisations on site to help. Photographer Newsha Tavakolian went to Ituri to document the lives of displaced women and the routine violence they confront.

On the way to Drodro

"The spring equinox—Nowruz, the Persian New Year—is in half an hour. They say that whatever you’re doing at the exact moment the sun finds herself right above the celestial equator defines how your life will unfold in the coming year. I am sitting in a car, traveling to [the village of] Drodro, on assignment for Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) for a documentary project about sexual violence."

People in the passing cars wear makeshift head coverings to protect themselves from the clouds of dust and dirt that surround the vehicles. We are driving on a muddy trail that squelches beneath the tires, a road that winds and twists, like snakes shedding their skin.

We stop yet again at another checkpoint, avoiding the bloodshot eyes of a soldier from one of the non-state armed groups active here. Some of them are just boys, armed and dressed in military gear. The back of a callused finger runs along my bicep, and my eyes chase the glimmer of light that bounces off a horizontal crack in the windshield.

Outside, the shrill squealing of pigs will not stop. I ask the driver to go faster, so we can leave them behind. The road splits, one way leading to the Lendu tribe, while we turn right toward Drodro, where thousands of displaced Hema people are living. Life goes on outside the huts, with the harvesting and drying of cassava the most prominent image as far as the eye can see.

Tsuya, a makeshift refugee camp, was set up in Drodro many years ago. Approximately 20,000 internally displaced people live there.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos

Three adolescent boys stand in a field just behind their huts in the village of Drodro, which, like much of DRC, is rich in natural resources. DRC 2021

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosWe arrive at the village. Even though Sunday mass is a few days away, there is a large gathering of people milling around a tall statue of the crucifixion of Jesus. We cannot stop to investigate, as we need to move on toward Drodro hospital, where I am due to visit with mothers who are malnourished and their young children.

People gather near a large cross by the main road in Drodro. They believe that Jesus is bleeding from the foot that has broken off the statue. The crowd grows daily because they think that a miracle is occurring and hope that their prayers will be answered.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosUnder the mosquito nets, small children wail and cry. I meet a little girl who doesn’t smile and—with help from one of the doctors—I ask her to become my assistant. She holds the light for me as I shoot photographs. Outside the building, people have gathered with their meagre supplies of local crops—cassava, bananas, and pineapples—making meals for their relatives staying at the hospital.

A woman who gave birth at Drodro hospital. Many women and children suffer from malnutrition because they lack adequate food. DRC 2021

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosDespite the country’s rich natural resources—including oil, diamonds, cobalt, and gold—the majority of the population of DRC remains impoverished. Millions of people are also forcibly displaced and exposed to physical and sexual violence on a daily basis. Much of the violence is unleashed by members of the military and ethnic militia groups, whose impunity encourages similar acts by members of the general public. Men in particular—whose primary victimsare women and children.

In the Ituri region of northeastern Congo, the conflict is especially severe between the farming communities of the Lendu people and the pastoralist communities of the Hema people. When three wounded Lendu youth are brought to the Hema camp by the MSF team to receive medical aid, members of the Hema community are quick to react. A group gathers around the MSF van, threatening the staff with violence if they treat members of the rival tribe here at the camp. Finally, the MSF team has to take these three injured youth to another hospital to avoid conflict.

Mamma Justine is the president of SFVS [Synergie des Femmes pour les Victimes des Violences Sexuelles], a coalition of women activists who support victims of sexual violence. She tells me that the normalisation of sexual violence is not merely the result of political instability in DRC. She goes on to talk about the existing cultural context that inspires the objectification of women. Evidently there used to be a long-standing tradition that prompted men to take their desired partner and lock her up in a room, effectively abducting her without asking her consent, and before speaking to her family about their possible union. Mamma Justine tells me that the situation is further complicated by false beliefs and superstitions that are used to justify sexual violence. Some even believe that having sexual intercourse with a virgin girl can clear a man’s body of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus).

People walk along the road to Drodro, as seen from inside an MSF vehicle.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos

A landscape of smoke and trees in the countryside around Drodro, an area rich in natural resources.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosConflicts without end

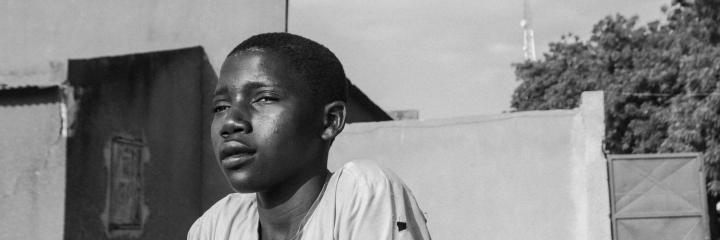

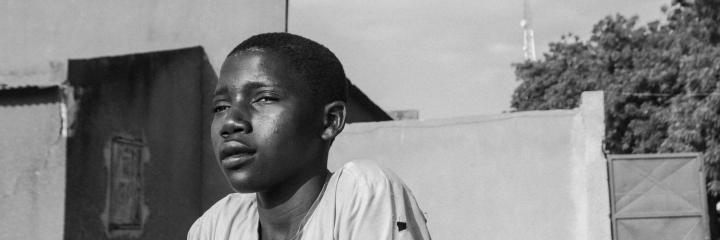

Three Congolese men in Drodro. Some men in the community, frustrated by high unemployment and lack of opportunities, unleash their anger by committing violence against women.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosThe land that is today part of DRC was colonized for its natural resources by the Belgian monarchy and called the Congo Free State. It was considered the personal dominion of King Leopold II of Belgium, becoming a Belgian colony in 1908. In 1960, following protests and an eventual uprising led by the Congolese people, the country gained its independence. But that did not mark the end of conflict in the country, which has seen years of chaos, coups, and insurgencies. The assassination of Patrice Lumumba in 1961—the first democratically elected prime minister of Congo—took away the possibility of forming a national central government that could work in the interest of the Congolese people and perhaps could have prevented decades of conflict in the country. The dictatorship led by Lumumba’s successor, Mobutu Sese Seko, lasted for 30 years, with support from the governments of the United States and France. In 1997, that regime was overthrown by opposition forces led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, in the wake of a military invasion by Rwandan forces that sparked the First Congo War and further conflicts.

The First Congo War (1996-1997), also known as Africa’s First World War, began as a civil war but quickly became an international conflict with the involvement of African countries like Rwanda, Uganda, Angola, and Sudan, as well as Western powers, especially France and the United States.

The Second Congo War began in August 1998 and ended officially in 2003 when the Transitional Government of the DRC took power. However, despite the signing of a peace agreement at the time, violence continues in different regions of the country, like eastern Congo where Ituri province is located. The Ituri conflict, which has roots dating back to the early 1970s, specifically refers to the intense violence that peaked in the region from 1999 to 2003, however armed clashes continue to this day.

Aggression as the only option

Honorine, the 48-year-old local relief worker on the left and Giselle (16) who visits the clinic regularly, on the right with a pair of plastic slippers with the word “VIP” printed on them.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosThe sunset is hauntingly beautiful when I meet Giselle, a tall 16-year-old girl with very short hair. She is wearing an off-white shirt, a long skirt, and a pair of plastic slippers with the letters “VIP” printed on them. Giselle says that her mother, after giving birth to her youngest child, lost her sanity and disappeared. Then, one night in 2018, rebels raided their village, killing almost everyone, including her father. Giselle and her eight young siblings were among the few who survived, which meant that she would have to step up and care for them. Two months ago, as she was fetching water along with five other women, Giselle fell behind because she was walking slowly with the heavy jugs. That is when she was grabbed by three armed men, who forced her to undress. They held a gun to her head so she would not make a sound during the assault. They raped her one by one, while the two others watched the road.

Bruised and in shock after the gang rape, Giselle somehow got back on her feet to walk the rest of the way. A man on a motorcycle saw how she struggled to walk and offered her a ride back to the camp. At the camp, an older woman saw Giselle’s state and, after hearing about the attack, urged her to go to the health centre to seek help. Unable to stand or walk properly for a while after her assault, Giselle still had to care for her young siblings. Giselle tells me that after her violent assault by three men, her first sexual encounter, she wants nothing to do with men. She has vowed to herself to never get married. She wants to continue her education so she can care for her siblings and help the women in her community. She speaks of her grief and vast loneliness, telling me that she feels so helpless without her parents, and that she misses her mother every day.

I explore the village, in awe of the beauty that surrounds me. The sky seems so vast here, yet feels extremely close to the earth, as if you can grab the cotton candy clouds merely by raising an outstretched arm. Once again, I find myself near the tall crucifix and the still growing crowd that moves around it. I ask someone about the reason for the impromptu gathering. They tell me that Jesus’s right foot has broken off the statue, and point to crimson liquid oozing out. The crowd seems to believe that Jesus is bleeding. I cannot linger here, as I need to move on to the health centre.

At the health centre

I meet Dr. Jean-Claude at the Drodro health centre, where they care for more women and children than their capacity allows. The health centre was previously supported by a non-governmental organisation called ACF (Action Contre la Faim). Recently, members of the Hema tribe set fire to ACF’s base and burned their vehicles, forcing the staff to evacuate with help from MONUSCO (Mission de l'Organisation des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en République Démocratique du Congo). Now ACF is no longer doing relief work in the area, which means that the women and girls who come to the health centre will need to pay for the medical aid they desperately require.

I ask Dr. Jean-Claude if he is comfortable communicating in English. He tells me that he can, to an extent. I ask him if he knows where I can find someone who works with victims of sexual violence. He tells me that he himself has been treating these women for the past 10 years, adding that many of them are assaulted by men they know, not necessarily by rebels. Women are often attacked by men from their own families or by other men in their own communities. Many of the victims are abandoned by their families; some are left with no choice but to seek shelter in the homes of the very men who have assaulted them; and some are sent to the nearby camps, which consist of a cluster of huts with cement floors.

There is not much to do at the camps. Some of the older children help their families by harvesting crops or fetching water. Women bear the brunt of the responsibilities, fetching water, collecting food or firewood, and working in neighbouring fields. Most of the sexual assaults happen during the trips these women must make in order to provide for their families. The same grounds where they are sent after their violent encounters may become the location of further violence.

Girls hide their faces from the camera on the road leading to the only place where people living in Rho camp can collect water.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosDr. Jean-Claude tells me that sexual violence is used as a weapon of war—a weapon of mass destruction. But men use and abuse women’s bodies to express their frustrations as well. He tells me that some men feel frustrated and powerless without decent jobs or a means of survival. Assaulting women can be their way of claiming some form of power. I think of one woman who was assaulted because she did not have the 500 francs—less than one US dollar—demanded from her.

It is such a stark contrast: this generous land, fertile, filled with tropical vegetation, and yet home to such unfathomable violence. I leave the health centre after Dr. Jean-Claude promises to put me in contact with a local relief worker who works closely with victims of sexual assault. There are so many women at the marketplace, moving about, making food, as their young children hold onto them. The few men who are around don’t seem to do much. DRC is like these beautiful women, violated constantly, giving to everyone who wants a piece of her dress, a piece of her body.

I pass by girls dressed in school uniforms—white shirts and navy skirts—walking shoulder to shoulder with boys who hold stacks of textbooks. They all walk by the deep green woods. It’s monsoon season, and shiny banana leaves still drip from the recent rain. I cannot help but wonder who among the group could unleash violence on these girls? Who—if anyone—would protect them?

Dr. Serge is a psychologist who has been leading a newly established program that aims to improve the mental wellbeing of victims of sexual violence in the region. He has been working with these women for the past year. He tells me that, in addition to the two most common emotions experienced by these women, namely shame and guilt, there are two general reactions to the experience of sexual violence here: complete mental breakdown or denial in the interest of forgetting.

I am reminded of the bishop’s words, when I asked him about the women and girls who waited their turn to confess. “There are things that burden them that they can tell no one but God,” the bishop tells me. How ironic that they ask him for forgiveness for crimes committed against them.

Dieudonné, 48, is a priest at the Drodro Roman Catholic church.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos“But trauma does not fade away. It festers inside the mind only to come back with a stronger, more destructive force,” says Dr. Serge. I ask him about the victims’ families, and whether they support the girls. He tells me that some do, which helps with overcoming the inevitable shame attached to being assaulted. But more families tend to banish the victims, leaving them with little choice but to live in exile at nearby camps, or even to be forced to seek help from the family of their assailants. How lonely and afraid they must feel, if their only refuge is staying with the same people who have turned their lives upside down.

I stand near the hospital waiting for them to take my temperature and allow me to enter. The broken thermometer keeps showing the number 32, as if checking a dead body. I hear shrill screams, and, as I enter, I see women, perhaps 10 of them, sitting on the stairway. The women are wailing with their arms outstretched toward the ceiling, mourning a fallen soldier. Another soldier wields his G3 rifle as he explains what has happened. But my interpreter tells me that he has overheard them say that the soldier died by suicide. They ask me if I want to see the body.

At the end of the corridor, women gather around the body. Wrapped in white sheets, the dead man’s eyes and mouth are closed as if in a deep slumber. The women throw themselves over the body and continue to wail. A few militia members—friends of the deceased—also join the crowd, crying for their fallen friend. I have no way of identifying the cause of death. But what difference would that make? These people have lost someone they loved dearly.

At the health centre, I meet with Honorine, the 48-year-old local aid worker who has been working there for the past three years. Honorine shows me a notebook filled with girls’ names. She tells me that every day at least five or six victims, mostly underage girls, many of them pregnant, seek their help. Many of these girls are also subjected to physical abuse by their own husbands. Honorine says that, at the camps, they encourage women to come by the centre to receive care if they are assaulted. The health centre offers check-ups, as well as medical care to prevent or deal with unwanted pregnancies and infections from STDs [sexually transmitted diseases], especially HIV. As we walk along the corridor, I see a packed room of perhaps 15 pregnant women, all waiting for their turn to be checked by the only attending midwife.

I ask Honorine why there is so much sexual violence. She shares Dr. Jean-Claude’s opinion, that rape is a means through which men exert power and seek revenge from the cruelty of life. For rebel fighters, of course, rape is a way to take power away from local men, tarnishing their honour by violating their women. I think about how a woman’s body becomes the site for this act of revenge. Many of these women are subjected to additional abuse because of the shame associated with their assault. Many are banished from their communities.

Nzale, 30, rests in Honorine’s lap. Honorine is a nurse who provides first aid and psychological support to women rape victims. Nzale was assaulted by rebels when she was out looking for food for her seven children and did not have the money that her attackers demanded.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosI come across the tall crucifix yet again. This time, in addition to his right foot, Jesus is missing both arms. My interpreter, Alphonse, tells me that the removal of the two additional limbs is an intentional act to prove to the crowd that the liquid is not blood, but the oxidized metal of the inner skeleton of the sculpture mixed with rainwater. I ask the resident bishop how he feels about the bleeding Jesus and the crowd it has attracted. He tells me that this kind of superstition is dangerous for their community and that he intends to put an end to the spectacle. During the Sunday service, with the church packed with attentive parishioners, the bishop warns the crowd of the ill effects of false beliefs and submitting to superstition. But outside, the crowd gathered around the crucifix seems unfazed. The next time I walk past the tall cross, the mutilated bleeding Jesus is gone, and so is the crowd that surrounded it.

Back at the health centre, I meet Gracian, a 52-year-old woman who works as an attending midwife. She has been working here since 2010. In a dark room with blue walls, Gracian sits at a desk covered with papers, documents, and files. The light from the small window illuminates her cramped workspace as she calls in the mothers-to-be one by one. I talk to her about the pregnant and displaced women that she cares for. “What is the most pressing issue for these women?” I ask Gracian. She tells me that right now, they need food and clothing more than anything else. Most of them only have one set of clothes—the ones on their backs. When they become pregnant, naturally their clothes will not fit them anymore. Most are not well-fed, and as a result, they bear small malnourished infants.

The women sit there listening in silence, without moving or doing much. Two of them catch my eye, as they look extremely young to be pregnant. You cannot tell whose pregnancy is the product of rape.

I go to bed in a bare room, protected by the flimsy mosquito net that surrounds me. It has been two years and 11 days since my father’s passing. All this time, not once have I spoken to or seen him vividly in my dreams. The moon is so big tonight, as if it hangs lower in the velveteen sky. Silence stretches over the camp area. Just as I fall asleep, my father is there, gently shaking me awake. “Dad, what are you doing here? Aren’t you dead?” I ask him. “So I am,” he replies. “Let’s go for a stroll.” As we walk along the muddy trail under the full moon, my father talks to me. I ask him questions to keep the conversation going. I ask him if he is happy, and he says he is. He tells me to keep a diary of all my thoughts every day. “But why, dad?” He takes out a small notebook from his pocket, flipping through its pages and showing me his notes and daily tasks scribbled in it: “Do you remember this?” “Yes, I do,” I tell him. In the morning, I am awakened by his loud whisper near my ear, and I wake up to find him gone. I am so confused when I wake up, as if I am surrounded by this heavy fog, like the thick mist that covers the horizon in Ituri. I think of how protected I feel by the memory of my father, even after his passing, and how thousands of women in DRC never find out what that feels like.

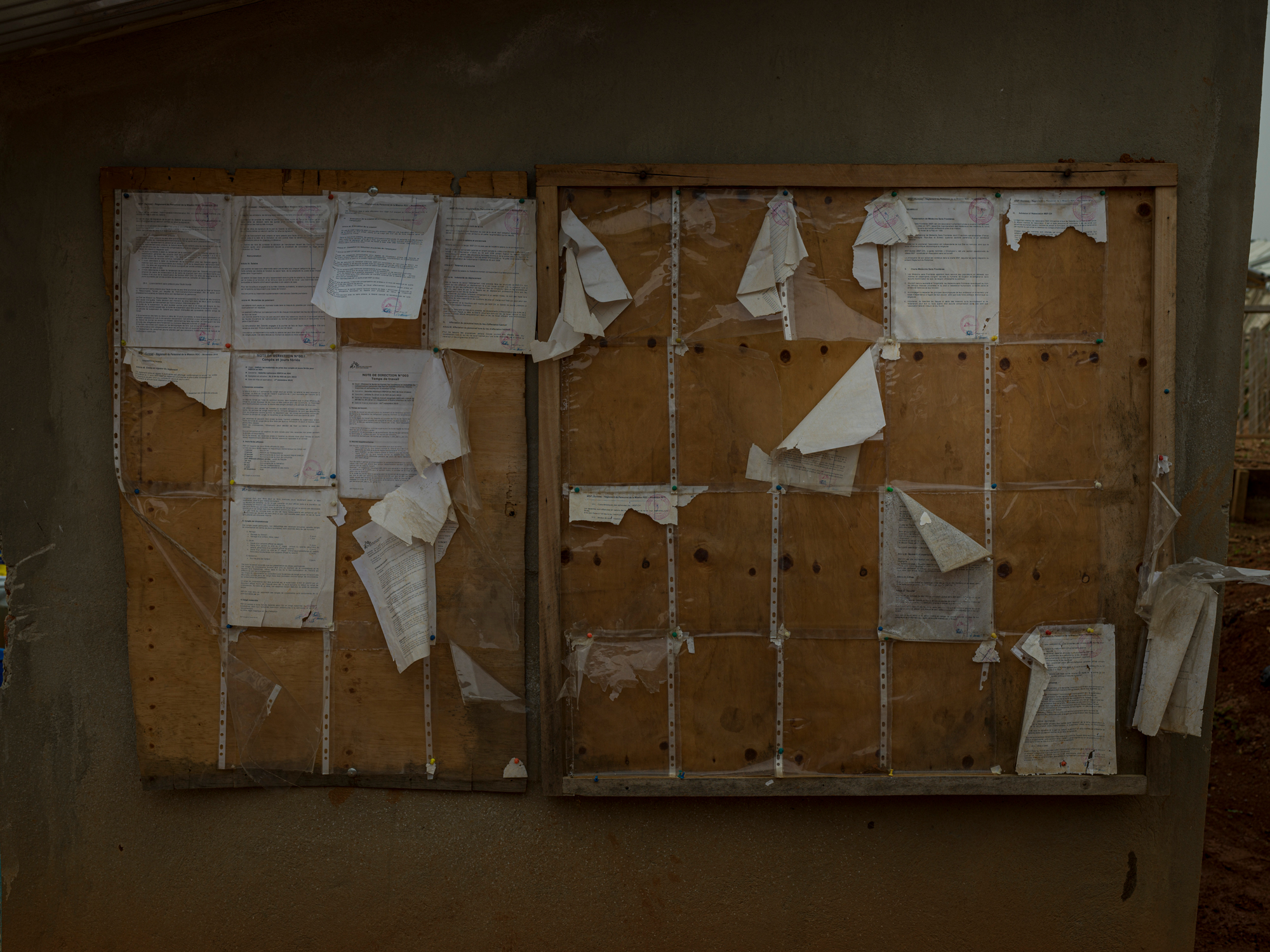

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum Photos

A hospital in Nizi where women and children receive medical care.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosAt the Drodro health centre, as the women wait to receive the care they need, they take turns sitting on the chair I have placed against the wall. They find little ways to keep themselves busy and distracted while they speak. A girl in a blue skirt and black top scratches the back of her hand. In the darkness of the blue examination room, the most striking details are the colourful accessories that adorn their frail bodies: a green skirt, a pink bracelet, a red scarf, a butterfly brooch, and a necklace with blue beads. I see and remember all these individual details, as does my camera. The women do not look directly at me.

When I first arrived in Drodro, I was worried that the women would avoid me, but now I am amazed that they seek me out so they can share their stories, knowing well that I am a photographer and not an aid worker. Most of them—if not all—are led to believe that they should be ashamed of themselves for having been assaulted. They live with guilt for a horrific experience that they had no control over. Yet, you cannot group all these women and girls together. No matter how common it might be, the collective experience of violence does not erase its individual impact. Each of these women and girls deserves to be heard.

Noella Alifwa and her colleagues at Radio SOFEPADI are here not only to listen to these stories, but to use them to raise awareness. Noella and a group of other women worked at a radio station here about 21 years ago. Together they founded an organisation through which they discuss sexual violence. Noella tells me that their collective has four major objectives: 1) to familiarize women with their rights; 2) to work towards creating peaceful communities where women can feel safe; 3) to advocate for better leaders; and 4) to teach women how to care for themselves, both in the immediate aftermath of being assaulted, and iover the longer term. Their organisation works on over 50 cases of sexual assault annually, and they continue to reach out and offer help. They do not believe that change can happen overnight. On the contrary, they are aware that because of the cultural context that objectifies women, and in the absence of a reliable legal system, slow and steady reform is the way to go.

I cannot help but be reminded of the woman who kept angrily interrupting MSF announcements that shared information about STDs and unwanted pregnancies caused by rape, deeming them blasphemous and wrong. I cannot fault her. Long-standing beliefs—no matter how harmful they are—require time and effort to fade away.

The last time I pass by the tall cross, Jesus is back on top. The statue is no longer bleeding, but the severed limbs have been reattached awkwardly. There is no crowd gathered this time.

Women walk along the road to Rho camp, the only location where people can go to access water.

© Newsha Tavakolian / Magnum PhotosBack on the winding dirt road, women walk along the trail, their bodies burdened with the heavy jugs of water and the thick bundles of branches they have to carry back to the camp. Most of them are dressed in colourful clothes made of African fabric (pagne) and adorned with the words huit Mars (March 8) and Journée Internationale de la Femme (International Women’s Day).

As I watch their swift progress, I wonder if a day will come that their March 8 dresses are not the only clothes they own, when they can be aware of and empowered by what the day represents.

Story by Newsha Tavakolian, co-authored by Sara Kazemimanesh

Latest photo-reportages

Greece: Trapped in island camps by Enri Canaj, 2020

Sudan: Refugees at the border by Thomas Dworzak, 2020

Honduras and Mexico – looking for hope at the end of the road by Yael Martínez, 2021

Mossoul, When The Birds Will Fly Again by Nanna Heitmann, 2021